Case of Drawers (detail of interior of drawer), Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1835, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1975.13863.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

This small case of 18 drawers was exhibited in 1986 at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition “Shaker Design,” and is one of the better known pieces in the Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon collection. It is remarkable in that each of the drawers in the two banks of nine drawers is a different height – gradually becoming deeper, drawer to drawer, from top to bottom.

Case of Drawers, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1835, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1975.13863.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

This small case of 18 drawers was exhibited in 1986 at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition “Shaker Design,” and is one of the better known pieces in the Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon collection. It is remarkable in that each of the drawers in the two banks of nine drawers is a different height – gradually becoming deeper, drawer to drawer, from top to bottom. Each drawer is divided into eight compartments resulting in a total of 144 compartments. (Fig. 2) Additional dividers were added to a few of the compartments in the upper drawers at a later date. The lower drawers have short bevels intended for paper labels. Several drawers retain these small printed paper labels – “No. 7,” “No. 9,” “No. 14,” etc. (Fig. 3) The numbers were probably keyed to some kind of catalog that indicated their contents. The proper left-hand side of the case has been altered and the back appears not to be original. The case may originally have been a built-in that had a piece of thin plywood added to its left side and a back put on when it was removed from its original location. It is also possible that the piece was once longer, maybe originally having more drawers or a cabinet attached to its left end. Whatever the original form, the case of drawers remains an impressive piece of cabinetwork.

Case of Drawers (detail of interior of drawer), Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1835, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1975.13863.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

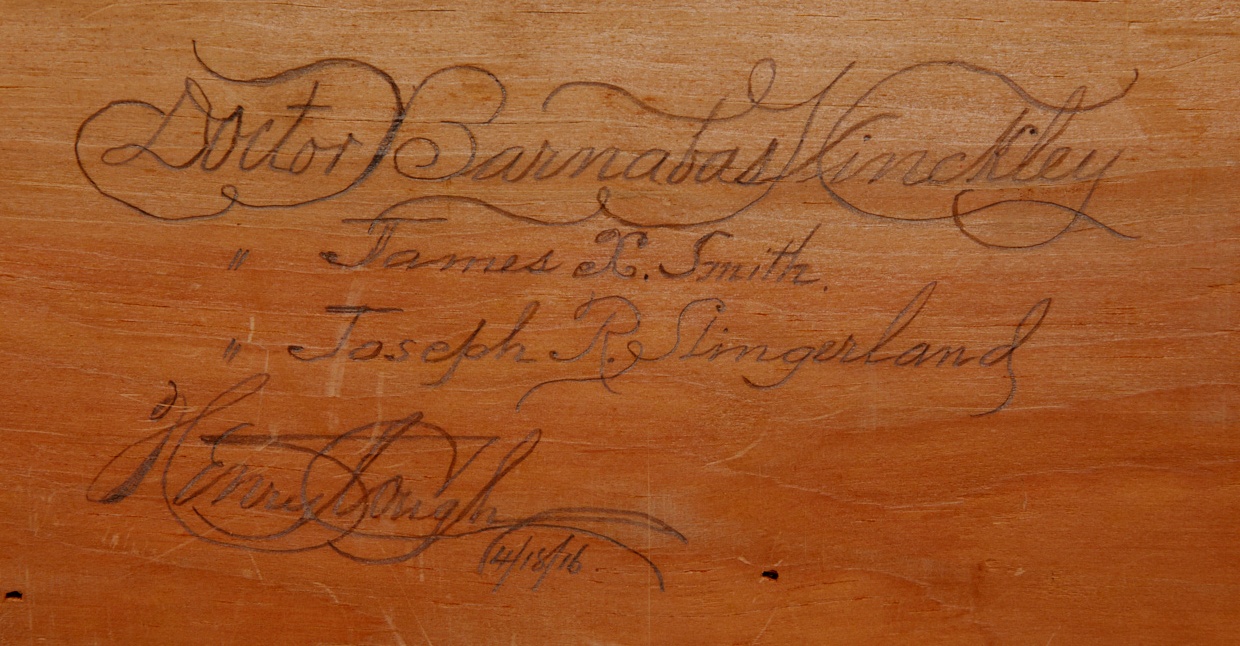

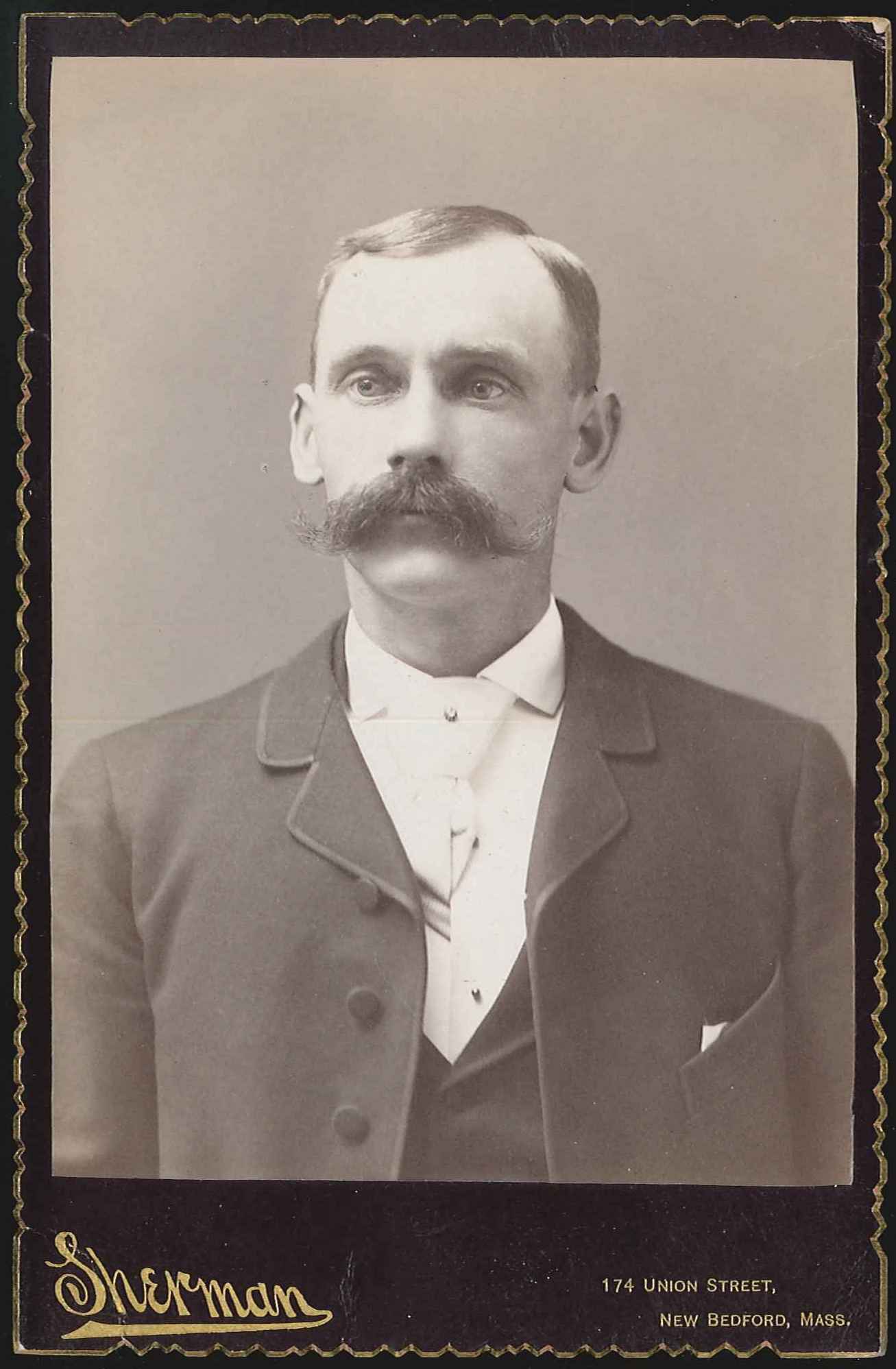

It is a not clear how the piece was originally used, but inscriptions on the bottoms of several drawers offer a few clues. On the bottom of one of the drawers the names of four Shaker brothers are written in pencil. (Fig. 4) They are: “Doctor Barnabas Hinckley, James X. Smith, Joseph R. Slingerland, Henry Clough.” The date “4/18/16” follows Henry Clough’s name. All four of these men were at one time in their lives associated with either medical treatment or the medicinal business at the Church and/or the Center Family at Mount Lebanon. Brother Barnabas came to Mount Lebanon as a young teen. By 1840 he had become a physician for the family. He was one of only a few Shakers privileged to an education outside of the community; he received a medical degree from the Berkshire Medical College in 1858. Brother James X. Smith was admitted to the Shakers in 1816 when he was ten years old. He worked as a farmer, as an herb presser, and later in life is described as a physician. Brother Joseph Slingerland also joined the Church Family Shakers as a child in 1855. He is known to have helped James X. Smith when Smith was a physician. Brother Henry Terry Clough (Fig. 5) was born in the fall of 1862 and was indentured to the Shakers before he reached the age of two. Henry was raised a Shaker and in his mid-20s went to work in the herb business with Elder Calvin Reed. In 1890 Henry decided to leave his Shaker home. Shortly after he left, he married Julia Mintie Dalton, whom he had known as a young Shaker sister. The two moved to New York City and eventually to New Jersey where Henry was a successful businessman. Around 1907, after having produced a family of five children, Henry and Julia began inquiring as to whether they might return to live with and work for the Shakers. By 1909 they moved back to Mount Lebanon and took up residence in what is now called Ann Lee Cottage at the Center Family. There Henry had responsibility for running the Shakers’ herbal medicine business.

Case of Drawers (detail of inscription of physicians’ names), Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1835, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1975.13863.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

It seems likely that the case of drawers was associated with the Shakers’ physicians order or those involved in the herbal medicine business and could have been used as an apothecary cabinet, a place to keep samples of prepared herbs, or a repository for medicinal labels.

Although one might assume the four names written on the drawer bottom were written by those who are named, there’s reason to think otherwise. First, they are all written in pencil when the Shakers often used pens for inscriptions. While the handwriting seems to vary from one signature to another, there is a consistent slant to the handwriting and occasional similarities in the letter forms being used. It also seems improbable that each successive person would have removed the drawers and turned them over and in doing so found the name or list of names to which to add their own. There is also some question as to why the signatures would have been recorded on the bottom of one particular drawer in the first place. While Brother Barnabas may have written his name on the drawer bottom, it seems unlikely that successive medical brothers would have thought or known to have added their names to the list.

Portrait of Henry Terry Clough, ca. 1890s, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1967.16069.48. Sherman, Bedford, MA, photographer.

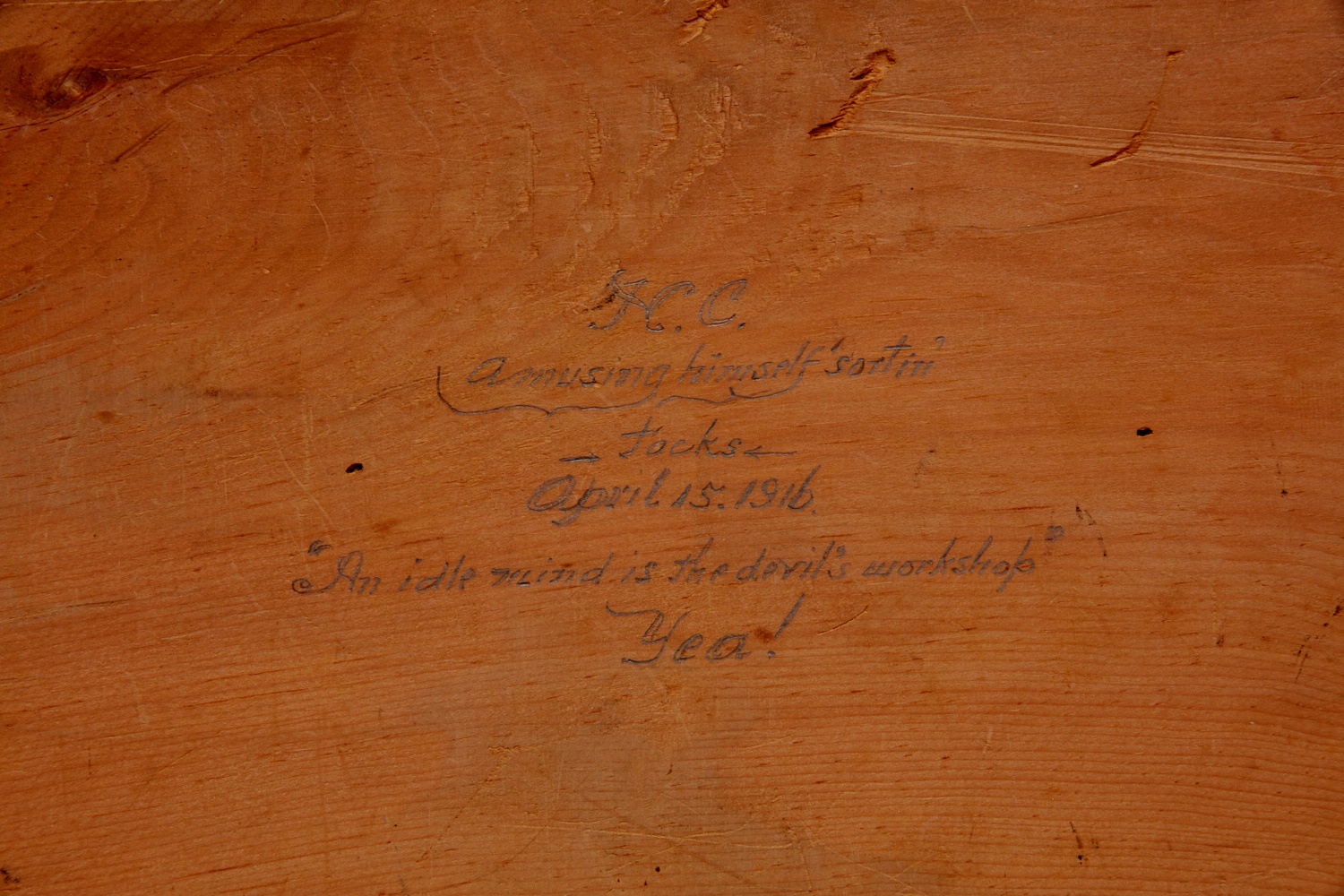

The last person listed, Henry Terry Clough, left two other inscriptions on the bottom of other drawers in the case. One reads (Fig. 6), “H. C. Amusing himself sortin’ tacks, April 15, 1916, ‘An idle mind is the devil’s workshop.’ Yea!” This suggests that although it was still being used in a medical workshop, the case’s purpose may have changed. It appears by this time to have become a home for various tacks, knobs, escutcheons, and other small pieces of hardware. The shadow of an escutcheon for a keyhole and other tack holes on the fronts of some drawers seem to confirm this change of use. (Fig. 7). A reasonable hypothesis is that Henry Clough who, needing a place to store such hardware, found the case of drawers, possibly still in its original location form and location, and removed it and repurposed it to house hardware. It was around the same time he was “sortin’ tacks” that Henry added his name to the list of brothers. Henry was an amateur photographer and some of his photographs and a collection of commercial photographs of Shaker subjects were given to the Shaker Museum by his widow, Julia Clough. Henry wrote on the back on many of these photographs and his handwriting shows that he also had an interest in calligraphy (Fig. 8). The Shaker Museum also has a wooden board carved with, “My Autograph ‘The sufficiency of my merit is to know my merit is not sufficient’ Henry Terry Clough,” that was either carved by Henry or caused to be carved by him (Fig. 9). His clear interest in handwriting does provide cause to consider whether it was Henry – who certainly had the opportunity – who created all of the inscriptions on the drawer bottoms of this case of drawers while he was “sortin’ tacks.”

Case of Drawers (detail of inscription), Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1835, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1975.13863.1. John Mulligan, photographer.