Selection of Paper Labels for Marking Objects in the Great House, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1833, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon, 1950.376.1

No single Shaker building provided a physical environment that harmonized more perfectly with the Shakers’ vision of what it meant to live outside the common course of the world than the “Great House” – the Church Family Dwelling – at Mount Lebanon. The architecture, furnishings, personal accessories, and conveniences of daily life were the pinnacle of […]

The Great House, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1871, Shaker Museum|Mount Lebanon, Accession Number: 1960.12583.1. James Irving, Photographer

No single Shaker building provided a physical environment that harmonized more perfectly with the Shakers’ vision of what it meant to live outside the common course of the world than the “Great House” – the Church Family Dwelling – at Mount Lebanon. The architecture, furnishings, personal accessories, and conveniences of daily life were the pinnacle of Shaker design as it reflected the Shakers’ spiritual life. “It is advisable for the center families in each bishopric, to avoid hiring the world to make household furniture…” states Part four, paragraph twenty-eight of the “Millennial Laws,” as revised in 1845, and it can be assumed that as the living quarters of the most central of all families in the most central of all bishoprics, the Great House was carefully furnished with little hint of worldly style and fashion. We will never know for certain, however, because on February 6, 1875, Charles Harris, a disgruntled employee at the family’s medicine shops, burned it all down. Harris set a fire that burned eight buildings at the Church Family and nearly destroyed several others, including the 1824 Meetinghouse. Later in the month he burned down the Herb House as well. As a result, even though the Shakers made every effort to save their belongings, we know of very few objects that can absolutely be associated with the Great House. Harris eventually was convicted of the crime, jailed, and died in prison at his own hands,

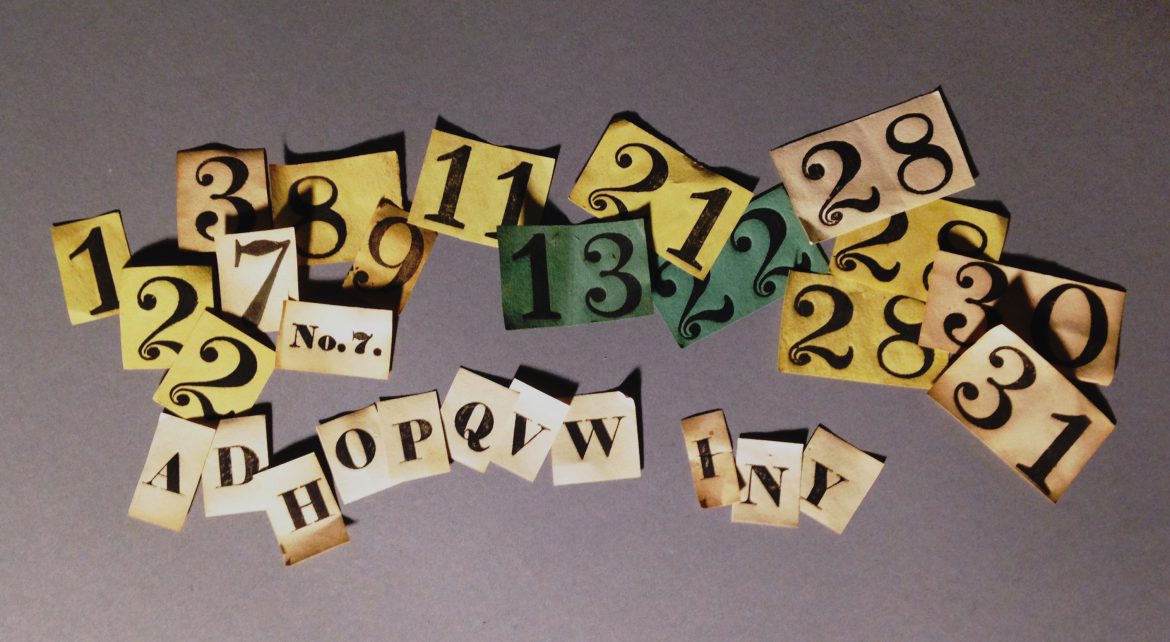

Selection of Paper Labels for Marking Objects in the Great House, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1833, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon, 1950.376.1

One object in the collection of Shaker Museum|Mount Lebanon related to the Great House is a box of paper labels with numerals and letters printed on them. The box and its contents were made in 1833 by Brother Isaac Newton Youngs (1793-1865). Brother Isaac, a resident of the Great House for all of his adult life, was a fastidious brother with a passion for order. He described how the paper labels were used in a December, 1833, letter to Elder Benjamin Seth Youngs, at South Union, Kentucky: “the rooms are all numbered, but not with any Showy sign or label—then we have large figures printed on paper about an inch in depth for which I made some types on purpose which we paste onto the furniture, chairs, brooms—store things, &c. &c. that belong to the several apartments which helps much to keep things in their place.” A few objects have surfaced over the years with Brother Isaac’s numbers pasted on them, including two books in the Museum’s collection, but most of the items must have burned. The books most likely survived by having been taken elsewhere before the fire. One, a Holy Bible printed by Isaiah Thomas, Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1802 is marked on the cover with the numeral “9,” and a copy of Testimonies Concerning the Character and Ministry of Mother Ann Lee (1827) in a blue paper binding is marked with a numeral “7” label. It is interesting to note that room “7” was Brother Isaac’s room until he was moved to another room in 1840. The box itself was likely kept in Brother Isaac’s workshop rather than in his retiring room, and thus survived the fire.

Holy Bible (Worcester, 1802) and Testimonies Concerning the Character and Ministry of Mother Ann Lee (Albany, 1827), Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon, 1950.3319.1 (Testimonies) and 1950.3312.1 (Holy Bible). John Mulligan, Photographer

The box itself is neatly made. About the size of a Shaker seed box, it is hand dovetailed with a lid with cleats to keep it from warping. It is divided into thirty-six compartments. On the inside of the lid, Brother Isaac inscribed, “December 10, 1833,” and is signed with his distinctive pencil flourish that includes this initial, “i. n. y.”

Compartmented Box with Numbered Labels, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1833, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon, 1950.376.1. John Mulligan, Photographer

In a eulogy to Brother Isaac written by Brother Elisha Blakeman in 1866, he describes this very useful Shaker brother: “His mechanical genius was remarkable. In him was combined, The Carpenter, Cabinetmaker, Clock and Watch-maker; which obligation he filled to the last. He many years did the Tayloring, and when needed, could turn Machinist, Mason, or anything that could promote the general good. Very many of our little conveniences which added so much of our domestic happiness owe their origin to B[rother] Isaac…”(1)