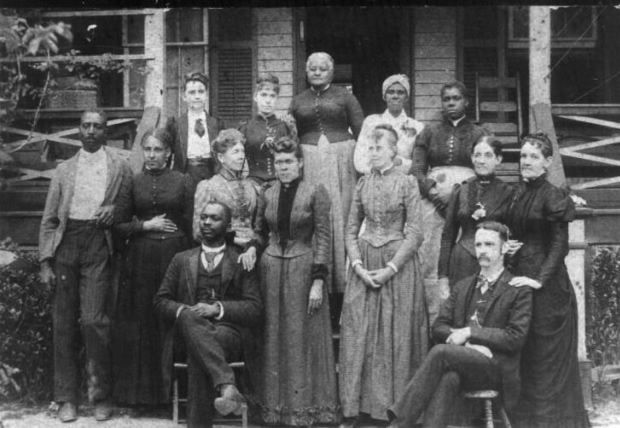

Schofield School staff, date unknown, retrieved from https://knowitall.org/photo-gallery/aiken-county-schofield-school

On April 3, 1885 the mercury reached 46 degrees Fahrenheit at Mount Lebanon’s North Family according to Brother Daniel Offord’s entry in the family’s garden journal. It was a mild cloudy Friday and the hired men were working at getting the year’s firewood cut, split, and under cover while a few of the brothers were working at the family’s saw mill. To […]

On April 3, 1885 the mercury reached 46 degrees Fahrenheit at Mount Lebanon’s North Family according to Brother Daniel Offord’s entry in the family’s garden journal. It was a mild cloudy Friday and the hired men were working at getting the year’s firewood cut, split, and under cover while a few of the brothers were working at the family’s saw mill. To what seemed to be an uneventful day, Brother Daniel added a curious note: “Sent a bbl of lamps tin ware literature &c &c to Martha Schofield.”

Schofield School staff, date unknown, retrieved from https://knowitall.org/photo-gallery/aiken-county-schofield-school

Martha Schofield was born in 1839 into a Quaker family in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Her parents were strong abolitionists who frequently had Reverend Edward Hicks and James and Lucretia Mott as guests in their home and on occasion were known to harbor fugitive enslaved people. As a young girl, Martha, strongly affected by these experiences, began teaching runaway enslaved people to read and write and when she turned 18 began her professional teaching career in Bayside, Long Island. In October of 1865, with the end of the Civil War, and in response to President Lincoln’s call to help enslaved people who had been emancipated, she moved to Edisto Island, near Charleston, South Carolina. Three years later, and after recovering from malaria or tuberculosis back at her family home, she returned south with her life savings and promises of support from people like her friend Susan B. Anthony and founded the Schofield Normal and Industrial School in Aiken, South Carolina, to serve the area’s freed enslaved people. A school building was completed in 1870 and with three teachers, including Schofield, the school taught and boarded 68 students. The school grew rapidly and focused on training young African Americans in the trades and to become teachers. In 1882 Schofield was able to build a large brick two-story schoolhouse but was in need of additional dormitory space to house an ever-growing population of students.

Schofield Normal and Industrial School, First (1870) and Second (1882) Schoolhouses from, South Carolina Bureau, The Augusta Chronicle, “Schoolhouse Inspires Students,” retrieved from http://chronicle.augusta.com/stories/2005/09/07/aik_1102.shtml#1.

An article appeared in the New-York Daily Tribune on February 19, 1885 concerning two young African-American men, Alfred W. Nicholson and Hampton Matthias, who were teachers at the Bettis School in Edgefield County, South Carolina. In an effort to keep ahead of their students they decided they both needed additional education so, while Matthias taught, Nicholson attended university and then when his course works was done for the year – they switched. Both had been students at the Schofield School and Martha Schofield took the opportunity of having two of her students featured in the Tribune to make an appeal for support for her school. In a February 26 article she expressed her concern about the challenge of accommodating an increasing demand for African American teachers. She wrote: “Here there is such a pressure behind us we dare not stand still; we are pushed on to new burdens, the completion of which is only seen by the eye of faith shining under the light of Divine guidance. We are being forced to erect a girls’ boarding hall…. The cost, with careful management, will be about $1500. Over $500 has been subscribed and the lumber is on the ground and paid for. No debt will be incurred. Carpenters stop when the money gives out.”

Eldress Antoinette Doolittle, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1880, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1962.13962.1,

It was apparently this appeal to which the North Family Shakers responded both in money and with a barrel of goods. In a letter to the Tribune published March 1, 1885, Eldress Antoinette Doolittle expressed her family’s respect and support for Martha Schofield’s work. She notes that they, the North Family, had been aware of her efforts in educating African American students for several years. With the letter, the North Family included a check for five-dollars to be sent on to Schofield to aid in the building of the school. Eldress Antoinette’s letter, transcribed below, addresses her experiences with formerly enslaved people who worked in the hotels in Lebanon Springs, New York, where she grew up until she joined the Shakers in her teens.

SHAKER AID TO NEGRO SCHOOLS.

WORDS OF ENCOURAGEMENT FOR MARTHA SCHOFIELD.

To the editor of The Tribune.

FRIEND: We read with interest the letter of February 26 from Martha Schofield addressed to the TRIBUNE, asking aid for building a schoolhouse in which to educate some of the colored people, to whom at present she seems to be giving her life labors unselfishly. We have watched her course of action several years, and have admired her as a heroine in striving, against persecution and many adverse storms, to be a friend to the friendless, and to uplift the lowly and oppressed who through circumstances over which they had had no control, have been subjected to the grossest wrongs, and suffered and sorrowed beyond language to portray.

I well remember when a small child of hearing a colored man say that if he could be a white man he would be willing to be skinned alive. He might justly have been considered a gentleman in manners and address, to some degree a man of letters, whose greatest fault seemed to be that his skin was very dark, and on that account he suffered many indignities from those of a lighter complexion. I also have a vivid recollection of an old slave called Venus who was employed as a washerwoman in some of our public hotels. Many hours I say by her side hearing her relate her sufferings at the South when under the lash of her cruel master. Her hands and fingers were ill-shapen and deformed. When she told me the wrongs inflicted upon her my young heart was deeply touched, and almost bled with sympathy as I saw the scalding, bitter tears course their way down her furrowed cheeks.

I remember those things in the dark days of our late Civil War and, while we deeply regretted the cruel effects of that war upon many households and the mourners who were bereft of loved one[s] who fallen in battle, yet the cries and groans of downtrodden, oppressed slaves were greater, piercing the heavens, and He who heareth the orphan’s cry and feedeth the ravens struck a blow that broke the strong chains that bound them, and the manacles fell! We watched with intense prayerful interest the events of those never-to-be-forgotten days, and now rejoice that there is a way open for the slaves, who were once thought to be almost soulless and devoid of intellect, gradually rising in the ascending scale of knowledge, moral worth and spiritual unfoldment.

We sent THE TRIBUNE five dollars ($5) [roughly $120 in today’s dollars] to aid in the erection of a schoolhouse above referred to in hopes that this small contribution, given in sympathy for the cause of freedom, may induce others to add thereto, and thus create a little fund that may be forwarded in safety to Martha Schofield, who we honor for her work’s sake. Sincerely, ANTOINETTE DOOLITTLE.

Mt. Lebanon, N. Y., Feb 27, 1885.

The Schofield School – incorporated into the public schools of Aiken, South Carolina and integrated in the 1960s – continues its educational mission. If Ms. Schofield responded to Eldress Antoinette’s letter and if the North Family continued to support the school is still to be discovered.