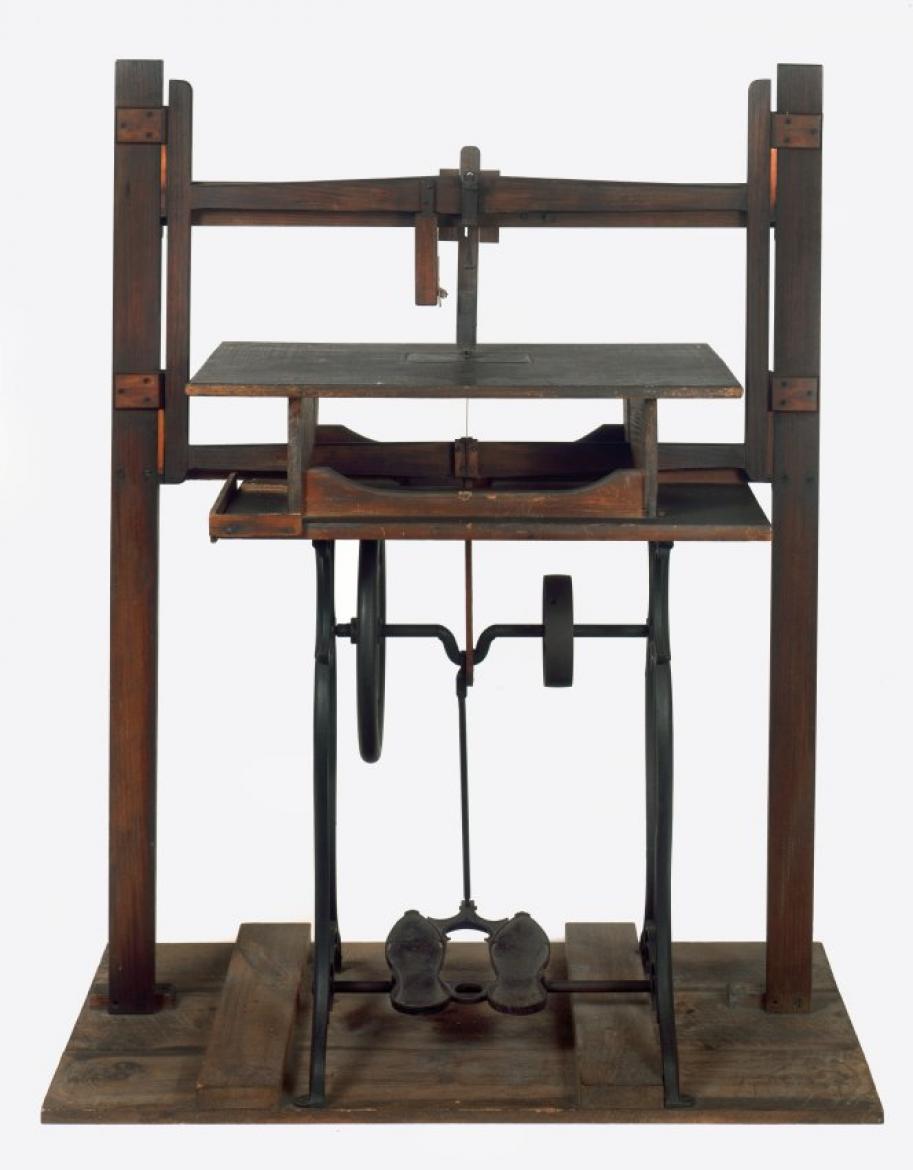

Scroll Saw, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1870, Shaker Museum: 1950.3856.1. Michael Fredericks, photographer.

In April, 2016, Shaker Museum presented its inaugural blog post, about the manufacturing of candied flagroot by the Shakers at Canterbury, New Hampshire. To ease the annual work of slicing hundreds of pounds of flagroot, they had repurposed an old sewing machine to slice flagroot by attaching a rotating cutting head to the business end of the machine. The Museum holds four sewing machines in its […]

In April, 2016, Shaker Museum presented its inaugural blog post, about the manufacturing of candied flagroot by the Shakers at Canterbury, New Hampshire. To ease the annual work of slicing hundreds of pounds of flagroot, they had repurposed an old sewing machine to slice flagroot by attaching a rotating cutting head to the business end of the machine. The Museum holds four sewing machines in its collection that have been modified by the Shakers to perform a job other than the one for which they were originally intended. In addition to the flagroot cutter, there are two small turning lathes and a scroll saw made from retired sewing machines. Power for each of these machines is provided by foot-operated treadle. The rocking treadle is connected in such a way as to either rotate a horizontal shaft that is, in turn, connected by a belt to turn a cutting head or pieces of wood mounted in one of the lathes, or, in the case of the scroll saw, to use the linear up and down motion of the treadle to drive the saw blade.

The scroll saw is usually used to cut thin pieces of wood. Because it has a narrow cutting blade and cuts with an up-and-down motion, it is able to cut curved lines through wood. The Shakers may have used this saw to cut the round and oval shapes for the tops and bottoms of bentwood boxes, measures, and dippers; the back slats, arms, and rockers for chairs; or the many shapes needed for the bases for poplarware trays, pincushions, and boxes. According to an advertisement the Shakers placed in The United States Gazette for the Country on December 8, 1813, they had been using “a saw for the purpose of sawing a circle, such as a Half Bushel, Tub, and Pail Bottoms, and Follies of Wheels of any description,” for the past 15 years. This type of tool was likely common in a number of Shaker workshops. The cast iron base upon which this scroll saw is mounted and by which it is powered, was made from the base of a mid-19th century Wheeler & Wilson sewing machine. While not identified as such on the piece, a search of the Historical Trade Literature Collection at the Smithsonian Museum easily located illustrations of Wheeler & Wilson machines that closely resemble the base of the scroll saw.

Allen Benjamin Wilson (1823-1888), working in Pittsfield and North Adams, Massachusetts, began designing a sewing machine in the late 1840s and, in 1850, patented his first machine. His machine caught the attention of Nathaniel Wheeler (1820-1893) who induced Wilson to come work with him in Watertown, Connecticut. Wilson’s first machine was completed in 1851 and sold for $125. The company, now the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Company, moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1856, but by then Wilson had retired from active participation in the company to live off a regular salary and money received for his patents. The company went on to manufacture over two million sewing machines before being bought out by the Singer Corporation in 1905.

The introduction of sewing machines to Shaker life at Mount Lebanon appears to have begun at the Church Family, as it was noted on June 18, 1853, in the North Family Deaconesses Journal that “Eldress A[ntoinette Doolittle] & Harriet [Bullard] go to the First Order to see their sewing machine.” This began a long series of visits by sisters from one family to another and one community to another to look at and try out a variety of sewing machines as family after family acquired their own machines. While it is not noted what kind of machine they went to see, on January 20, 1854, “Peter [Long] went to Pittsfield & bro’t home a new sewing machine, Wilson kind, cost $125.” Although the shape of the base and the driving mechanism for the Wilson sewing machine remained the same for a number of years, it is possible that the sewing machine brought home by Brother Peter Long provided the base and driving mechanism for the scroll saw in the Museum’s collection.

Scroll Saw, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1870, Shaker Museum: 1950.3856.1. Michael Fredericks, photographer.

The Shakers’ conversion of the sewing machine mechanism to power a scroll saw is pretty straightforward. Instead of having the foot treadle convert linear motion to the rotary motion needed for a sewing machine, the mechanic who built the saw merely attached a vertical rod next to the vertical rod from the treadle to drive the saw blade up and down. An interesting feature of the saw is that as the saw goes up and down it is attached to a wooden cylinder mounted next to the moving blade that, as it goes up and down, pumps air into a leather tube that, in turn, blows away the dust created by the saw.

The Museum purchased the scroll saw from the craftsman George Roberts (1874-1953) in June 1950. Although Roberts was never a Shaker, he used, and later acquired, the woodworking tools and machines of the Church Family to manufacture Shaker-style furniture and oval boxes. The boxes made by Roberts were sold in the Shaker store. By 1947 when the last Shakers left Mount Lebanon and the demand for Robert’s products for their store declined, he decided to sell and later give a number of the tools and machines he had acquired from the Shakers to Shaker Museum. The scroll saw was the second artifact acquired from Roberts. Shaker Museum founder John S. Williams, Sr. purchased it in June of 1950.

What a lucid, informative blog! Hoping to be exposed to the entire series, and perhaps even new entries.

Thanks so much to Jerry Grant!