Interior of Flour Chest Showing Labels for Bins, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1850-1880, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1950.471.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

This red-painted flour chest in the Shaker Museum collection was acquired from the North Family at Mount Lebanon, a fact that’s backed up by a 1938 photograph of the interior of the North Family’s Wood House. In that photograph the flour chest sits behind, and is nearly obscured by, a table saw and a grindstone. The giveaways that this is […]

Flour Chest, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1850-1880, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1950.471.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

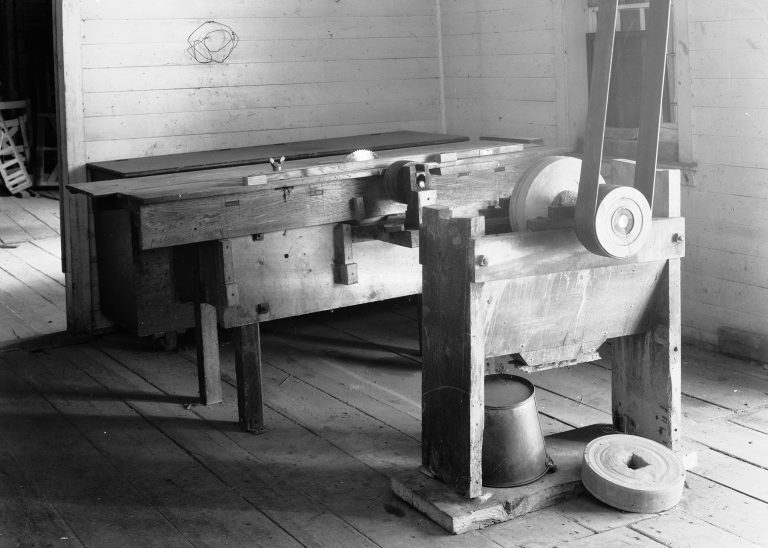

Interior of a North Family Wood House, June, 1938.

This red-painted flour chest in the Shaker Museum collection was acquired from the North Family at Mount Lebanon, a fact that’s backed up by a 1938 photograph of the interior of the North Family’s Wood House. In that photograph the flour chest sits behind, and is nearly obscured by, a table saw and a grindstone. The giveaways that this is the same chest are the four visible hinges on the top of the chest indicating that the lid is split into two sections, and the rather prominent casters used to roll the chest. These features, along with its general dimensions as they appear in the photograph, provide strong evidence that it is the same chest.

Interior of Flour Chest Showing Labels for Bins, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1850-1880, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1950.471.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

Interior of Flour Chest Showing Labels for Bins, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1850-1880, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1950.471.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

Each of the chest’s lids cover two partitioned compartments. The undersides of the lids are labeled in hand-painted letters: Rye, Middlings, Course Flour, and Fine Flour. All were used in baking. Rye flour is mixed with wheat flour to make rye bread. Middlings are the parts of the wheat kernel – the bran and sometimes the germ – that are often sifted out of milled wheat flour. Middlings are occasionally added back into bread for additional fiber and protein. Coarse flour usually refers to whole wheat flour – sometimes called Graham flour after Sylvester Graham, a 19th century advocate of vegetarianism, temperance, and eating only whole grain flours. Fine flour is what is left when all of the bran and germ are sifted out of milled wheat.

Elder Frederick W. Evans, North Family Elder for 57 years, is known to have been very particular about bread and how and from what it was made. In 1877 he wrote a letter to Brother Albert Lomas, editor of the The Shaker, commenting on making bread:

The wheat is the starting point. The wheat must be home ground, or you will not have homemade bread. We might as well go to Moody and Sankey for pure Christianity, as to go to a worldly miller with our wheat to grind; much less to buy the flour to make Shaker whole wheat, or coarse ground, unleavened bread.

He follows this caution with a recipe for Shaker whole wheat bread.

The Church Family built a substantial grist mill in 1824 and for years was able to produce flour for all the Mount Lebanon Shaker families. For a number of years they employed millers from the outside world and often had trouble keeping them. It may have been that by the time Evans wrote his commentary on wheat bread he was concerned that the millers were not supplying the family with proper flour for Shaker bread. Sometime in the early 1880s the North Family created a small grist mill inside their 1854 Wood House. By this time the family had largely switched to coal for heating and some of the Wood House was available for other functions. At the south end of the building the Shakers created a new modern laundry. The new laundry required power for the new machinery they installed. That power came from piping water under considerable pressure from a reservoir they had built in 1875 to supply hydrants to protect the family from fire. This water source was extended into the cellar of the Wood House to operate a ten-horsepower Baccus Water Motor. The Shakers soon found additional uses for the power supplied by the water motor – one of which was to power the equipment necessary to operate the grist mill.

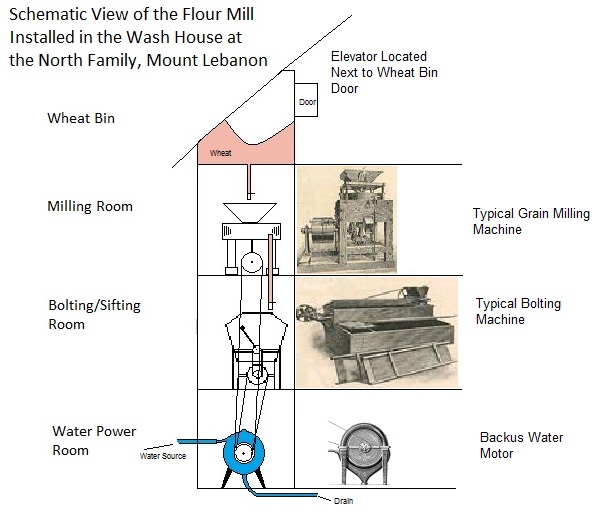

Schematic Illustration of the Grist Mill in the Wood House, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY. Museum staff.

The grist mill was constructed vertically in small rooms adjacent to the laundry and directly over the water motor in the cellar. The rooms were also next to an “elevator” that was used to take damp laundry from the wash room in the cellar to the attic when it needed to be dried indoors. While the date the Shaker built their grist mill is not known, it is known that on February 6, 1884, a carpenter “finished the wheat bins in the wood house loft.” The wheat bin is located in the Wood House attic directly over the room on the second floor where the grindstone was located. The bin could be filled from bags or barrels of wheat brought up the elevator and could be released down a wooden chute from the bin directly into the hopper of the grindstone. Flour and its more undesirable by-products traveled from the grindstone through another wooden chute to the room directly below where they were fed into a sifter or bolting machine that separated middlings from fine flour. For coarse flour, the ground wheat was not bolted, leaving all of the bran and germ in the flour – much to Elder Frederick’s liking. Both the grindstone and bolting machinery were powered by the water motor. The various flours produced in the mill needed to be stored in separate bins – therefore there was need for a large flour bin in the Shakers’ wood house.

It is not known when the milling equipment was removed from the Wood House. It was apparently gone prior to 1940 when A. K. Mosley measured and drew the Wood House floor plan for the Historic American Buildings Survey. There is considerable evidence still intact in the building that supports the description of the grist mill. A tin-lined square funnel in the floor of the wheat bin is open directly to where it appears the grindstone was located. Holes in the floors remain where belts from the water motor traveled to operate both the grindstone and the bolting machinery, and the wooden chute that once brought ground wheat into the bolting machine remains in place. The disposition of the equipment has yet to be discovered.

I appreciate the affectionate scholarship that went into this report. Tom Pavlovic