Last spring, through the efforts of Darryl Thompson, the current authority on varieties of fruits and vegetables developed by the Shakers, the Shaker Museum received a rooted cutting from a gooseberry plant that is thought to be a direct descendent of a variety of gooseberry developed at Mount Lebanon in the mid-1840s. Not yet being […]

Last spring, through the efforts of Darryl Thompson, the current authority on varieties of fruits and vegetables developed by the Shakers, the Shaker Museum received a rooted cutting from a gooseberry plant that is thought to be a direct descendent of a variety of gooseberry developed at Mount Lebanon in the mid-1840s. Not yet being certain where the gooseberries should be planted at the Museum’s Mount Lebanon historic site, the care of the plant was taken on by a staff member – albeit a staff members whose horticultural skills have not been fully vetted. Although the plant seemed to thrive through the summer, by fall it had lost most of its leaves and seemed to have gone dormant long before other foliage was doing the same. Concern set in as the once-green shoots turned into a dried stick through the winter months – but early in spring to the surprise and delight of its caregiver, small green buds and leaves began to appear and the gooseberry plant is now in full leaf and beginning to develop blooms – gooseberries to follow?

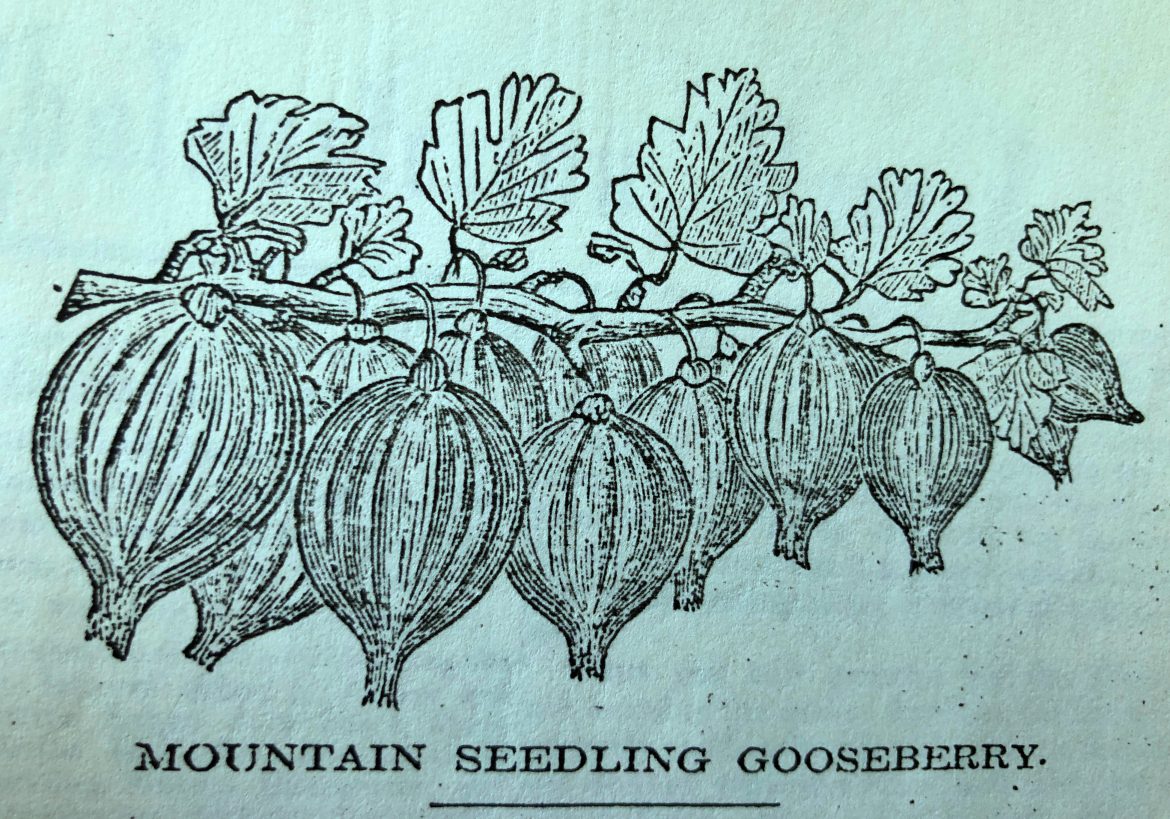

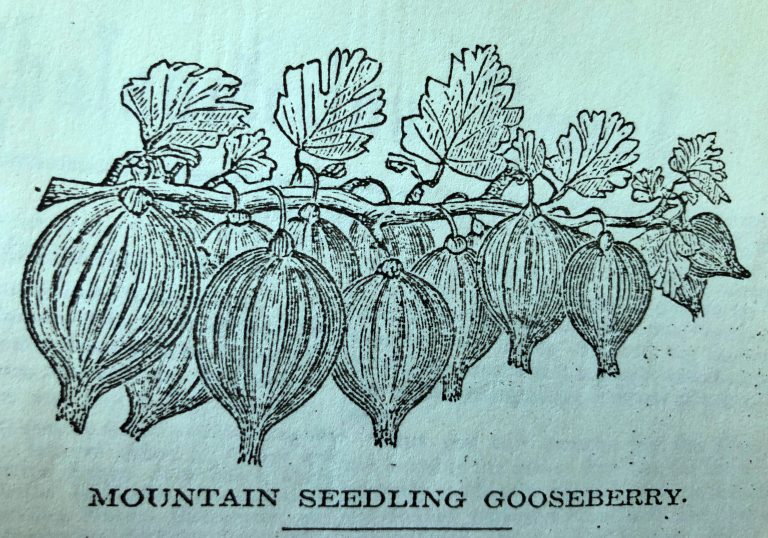

Mountain Seedling Gooseberry, staff photograph.

Mr. Thompson, who grew up with the Shakers at Canterbury, New Hampshire, and worked with Shakers and Shaker history most of his life, became interested about 30 years ago in the plant varieties they developed. Since then he has tracked down surviving examples of a number of these plants and returned them to Shaker villages where they were developed, cultivated, and marketed by the Shakers.

The gooseberry plant that Mr. Thompson secured for the Shaker Museum is a variety named by the Shakers the Mountain Seedling Gooseberry (also known as the Mountain Seedling of Lebanon). The Mountain Seedling Gooseberry became totally extinct in the United States. However, the Shakers had shipped it to Europe where it remained in cultivation all through Germany and Denmark. Mr. Thompson located an identifiable example of the plant growing in the horticultural collection of the University of Denmark. In 2004 they provided budwood – a section of the gooseberry plant stem with buds suitable for propagating – to the U. S. Department of Agriculture’s horticultural center in Beltsville, Maryland. They made cuttings and rooted them. Those cutting were sent on to the National Clonal Germplasm Repository in Corvalis, Oregon and cared for in quarantine for six years. Mr. Thompson secured a sample plant from that facility in 2010, and after 17 years of searching and letter writing, watched the plant go in the ground at Canterbury Shaker Village. It is a cutting from those plants that Mr. Thompson has provided for the Shaker Museum.

The gooseberry is not a particularly popular berry in the United States. Here, with an abundance of other berries – currants, blackberries, black raspberries, raspberries, and strawberries – they have never sustained gardener’s interest in the way that they have in places such as England where they are still accepted as a table fruit. Because gooseberries begin to turn bad soon after they have fully ripened, people in the U. S. tend to harvest them before they fully ripen, at a point when they are still quite tart with a surprisingly sweet aftertaste, and prepare them by adding a significant amount of sugar. In other places, people choose to let them ripen and find that they are semi-sweet with a flavor of a mild grape. There are several challenges to its cultivation as well. Native to Europe, the gooseberry is susceptible to a mildew particular to the U.S. In addition, here in the U.S., two varieties of gooseberry – the Houghton developed in 1833 by Abel Houghton of Lynn, Massachusetts, and the Downing developed from and thought superior to the Houghton in 1855 by Charles Downing of Newburgh, New York, so dominated the market that most of the other 209 varieties of gooseberry listed by U. P. Hedrick in The Small Fruits of New York (1925) withered in the marketplace. And finally, gooseberries are a host for the white pine blister rust that, while not harmful to gooseberries, is quite destructive to white pine trees. As a result, with heavy lobbying from the timber industry, gooseberries were banned early in the 20th century and great efforts were made to eradicate them from pine forests. By 1966, with the development of resistant pines and the discovery that the blister had several other hosts, the ban was lifted, but by that time what little interest the American taste bud had for gooseberries had all but disappeared.

The Mountain Seedling Gooseberry was developed at Mount Lebanon by Brother Philemon Stewart. While there is much to say about Brother Philemon – his uneven temperament and mental imbalance, his apparent quest for power and authority in Shaker society, and his perception that he would never measure up to the ability of his older natural brother Elder Amos Stewart – he may be recognized as an excellent horticulturist. In 1846, Brother Philemon discovered a wild gooseberry plant growing at Mount Lebanon that seemed different from the others around it – apparently it was free from a mildew that attacked many European varieties that had become the common wild gooseberries of the New England woods. After spending a number of years improving the gooseberry he was apparently ready to take it to market by mid 1850s. By this time he was sending samples to horticultural magazines and writing that the variety was available from the Shakers. For example, in September, 1856, he published in The Cultivator the following:

MOUNTAIN SEEDLING GOOSEBERRY.—Our friend, P. STEWART, of the Shaker family, at New Lebanon, has sent s sample of a gooseberry which he has cultivated for some years, and which he calls the “Mountain Seedling of New Lebanon.” It was discovered growing wild about ten year since, and has improved by cultivation from year to year. The bush is said to be a rapid grower and very productive—the berry is of good size and fair quality, and has never been known to blast or mildew, a quality of great value.

An article in Moore’s Rural New Yorker from April, 1858, describes the positive characteristics of Brother Philemon’s berry as:

being of a dark-purplish color, good flavor, and rather less than medium size, though larger than Houghton’s Seedling…This gooseberry we have seen and tasted but once, and though we don’t like to express a very decided opinion on so short an acquaintance, we think well of this variety. As it is native and does not mildew, and is larger and finer than any native sort now known, (except perhaps CHAS. DOWNING’S new seeding,) it will no doubt, be a decided acquisition.

One can see the writing on the wall as the Mountain Seedling is compared to the two preferred varieties of gooseberry available to those who wanted to raise them. However, the berry did have its strong defenders. Edward Y. Teas wrote to the Cultivator and Country Gentleman in October, 1860, saying:

I have had it bearing three years, and am highly pleased with it. The plant is of a robust habit, often growing five to six feet high; branches upright and strong; leaves deep glossy green, and very large; the berries grow in clusters of three of four,…. color of the berry, dull red; quality equal to Houghton. The plant is very productive, and never mildews. It is undoubtedly a native, of the same type as Houghton, and more valuable than that fine sort, on account of it fine size and the more vigorous and upright character of the plant.

Teas, operating a nursery in Richmond, Indiana, at his writing continued to carry the Mountain Seedling Gooseberry in this catalog into the early 1900s, so although Brother Philemon, moved into the spirit world in 1875, his horticultural work continues.

Mountain Seedling Gooseberry, Moore’s Rural New Yorker 9 (April 24, 1858), 135.

There is apparently enough descriptive material about the character of the Mountain Seedling Gooseberry to make an evaluation once the small plant now showing its blossoms grows to its full potential, hopefully, back at its source on Lebanon Mountain.

Wonderful detailed text-

Esoteric but engaging.

I had not known the Shakers, inventive capacities extended to fruit.