Raccoon Fur Mittens, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1880s, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1957.8294.1a,b. John Mulligan, photographer.

On February 6, 1875, Charles Harris, a disgruntled hired man, set a fire that claimed eight buildings at the Church Family at Mount Lebanon. The buildings, including the family dwelling and several workshops, were uninsured and the loss was estimated at over $100,000. Even with substantial support from many other Shaker families, the Church Family and, in […]

On February 6, 1875, Charles Harris, a disgruntled hired man, set a fire that claimed eight buildings at the Church Family at Mount Lebanon. The buildings, including the family dwelling and several workshops, were uninsured and the loss was estimated at over $100,000. Even with substantial support from many other Shaker families, the Church Family and, in fact, the Mount Lebanon community never fully recovered from the disastrous fire.

In response to the fire, Shakers at Mount Lebanon did what Shaker always seem to do – they doubled down their effort to recover from the loss by working harder. In the first few years, Mount Lebanon Shakers initiated several new businesses that they thought would produce income to aid their recovery. By far the most lucrative business to emerge during this period was the manufacture of proprietary herbal preparations for non-Shaker companies. Well known companies such as Lyman Brown and A. J. White made use of the Shakers’ medicinal laboratory and well-disciplined and trained work force, and even the Shakers’ name, to make and market their products. Several other similar contractual arrangements made use of the Shaker work force to make product primarily marketed by non-Shaker businesses.

Raccoon Fur Gloves, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1880s, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1950.3327.1a,b (gloves). John Mulligan, photographer.

One of the more interesting products to have its beginnings during this period was knitted hand-wear – gloves, mitten, and wristlets – made from a yarn that was a blend of silk and raccoon fur. From an 1877 entry in a Church Family deaconesses’ journal – “Return from N. Y. The business has been to get Coon Skins. Fur Gloves is becoming the rage of the season” – it appears that gloves and mittens knit from animal fur may have become a fashion fad of the day. It appears that most of the raccoon fur gloves and mittens made by the Shaker sisters were sold to a merchant, Samuel Budd, in New York City. Budd was a well-known manufacturer and purveyor of men’s wear. It is yet to be discovered whether the Shakers approached Budd to purchase their gloves and mittens or Budd sought out the Shakers to make this product for his store. There is also little information about where the Shakers may have learned how to make this product. Another entry in Shaker journal states – “Jane Morris came here to show how to put the fur & silk together for gloves.” Sister Jane Morris, a Shaker from age 15, was from the Shakers’ Second Family and at the time this comment was made, in December, 1876, was in her late 60s and known as a skilled spinner. The Shakers’ work on these items provides an example of the Shakers’ persistent effort to improve their products, their manner of making them, and their finances.

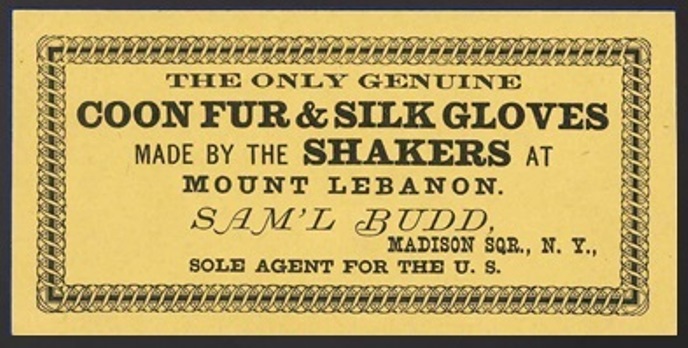

“The Only Genuine Coon Fur & Silk Gloves Made by the Shakers at Mount Lebanon. Sam’l Budd,” New York, NY, ca. 1880s, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1950.4267.1. Staff photograph.

The manufacture of raccoon fur gloves and mittens began with the acquisition of raccoon fur. There is no evidence the Shakers tried to supply themselves with raccoons by hunting or trapping; within the first year this yarn was being made the Shakers were purchasing raccoon pelts – “skins” the Shakers called them – in New York City. The Shakers often purchased from one to three hundred skins each year. The skins were untanned and therefore dry and stiff. The tails on the skins were removed and processed separately. The tailless skins were soaked and limed. The soaking made the skins pliable and the liming broke down the proteins that held fur tight to the skin. Raccoon fur has two types of hair – coarse guard hairs that protect the raccoon from the elements by shedding water and a soft thick inner fur that supplies insulation. The Shakers had to pick the former from the skins since the guard hairs did not spin well and would have made the yarn prickly. Once de-haired, the fur was pulled from the skin and set aside to dry. From here, the processing was not much different from that used to prepare wool for spinning. The fur was carded to straighten the fibers and blended with silk to increase its strength. This blend was then, in the beginning, hand spun into the knitting yarn.

After a few years of hand carding the fur and silk, on January 24, 1878, Sisters Mary Hazard and Sarah Ann Spencer took their fur and silk to a carding mill in the town of Hancock, Massachusetts, to “experiment on carding fur ready for spinning. They found it a success and surmised that this advancement would “give great impetus to the fur job.” The mill was owned by Sister Mary Hazard’s father Rodman Hazard.

In 1878, the second year of fur glove production, the sisters made 28 pairs of fur gloves. By 1883, “The Sisters have Orders for 30 pairs of gloves more, making 230 pairs.” This increase in the demand led the sisters to experiment with having the carded fur spun by machinery, but their attempts to do so at Rodman Hazard’s mill failed. They, however, had favorable results at a mill in Hinsdale, New York, and continued having their yarn prepared there – ready to knit.

The raccoon fur business, especially the preparations of the skins, by all accounts was not the most pleasant work for the sisters. The work was physically strenuous and the skins often dirty and greasy. In 1884 a sister recorded that they, “Wash the old clothes worn and rags used on the skins &c.” However, all this work seemed to be worth it, as summarized in a comment made on August 30, 1887: “Sisters finish fur pulling, pulled 288, Skins, & it averages a pair of gloves to a skin, & some more, say nearly 300 pairs of gloves, these sell at $5.50 per pair at wholesale, I believe, & $6.50 at retail.” At almost $190 in today’s dollars, a true luxury item!

Raccoon Fur Wristlets, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1880s, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1957.8295.1a,b. John Mulligan, photographer.

The raccoon fur glove business continued on into the first decade of the twentieth century but seemed to be at its peak during the 1880s and 1890s. While gloves and mittens were the mainstay of the business, the sisters also knit hats, wristlets, and leggings. The Museum holds in its collection examples of gloves, mittens, wristlets, and a hat.