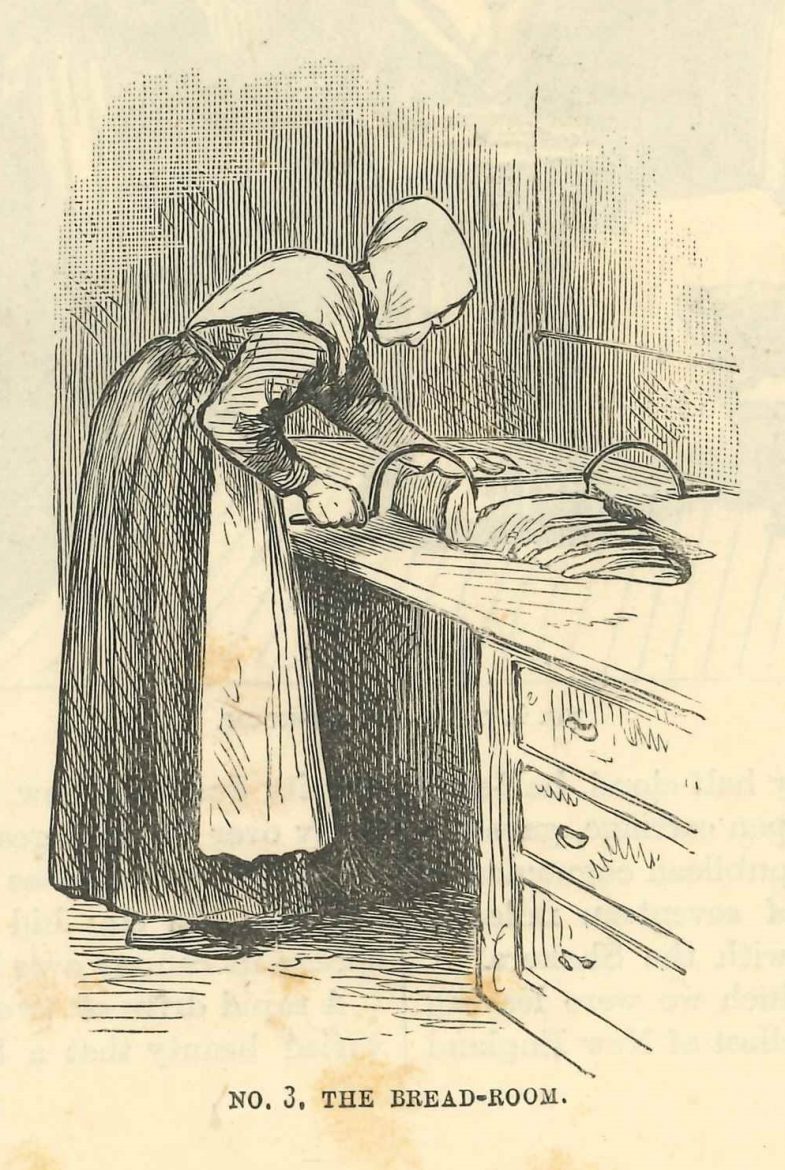

“The Bread Room,” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly, 20 (December, 1885), 663-670. Joseph Becker, illustrator.

Following our earlier post on a Shaker flour chest, the question was posed, “What was so special about Shaker bread and why did they go to so much trouble to grind the flour?” There are many recipes for Shaker breads and not many had the stringent specifications demanded by Elder Frederick Evans at Mount Lebanon’s North Family. His insistence on the importance of good […]

Following our earlier post on a Shaker flour chest, the question was posed, “What was so special about Shaker bread and why did they go to so much trouble to grind the flour?” There are many recipes for Shaker breads and not many had the stringent specifications demanded by Elder Frederick Evans at Mount Lebanon’s North Family. His insistence on the importance of good bread was epic. He thought wheat should be grown, harvested, and ground into flour – leaving all of the bran and germ in the flour. “The sisters insist,” he wrote in an article in an 1877 article in The Shaker, “that the unleavened bread cannot be made from the fine ground, or mercantile flour – I believe it. I quite agree with the God of Israel, that the first step in the work of human redemption is to make and eat good bread.”

“The Bread Room,” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly, 20 (December, 1885), 663-670. Joseph Becker, illustrator.

Elder Frederick was born in England and spent his youth there living on a farm. He wrote about how those days affected him in his autobiography (Elder Frederick W. Evans, Autobiography of a Shaker, and Revelation of the Apocalypse. Albany: Charles Van Benthuysen & Sons, Printers, 1869.) “I was hardy and healthy, and liked to work; I barely knew my letters, and detested paper books. I had not been poisoned with saleratus [baking soda], or American knick-knacks or candies; nor with American superfine flour bread.” As he found that his childhood diet served him well in rarely becoming ill, he encouraged the North Family to keep a vegetarian diet and to eat only simple unleavened whole-wheat bread.

The Elder’s recipe for bread was Shaker-simple:

He was so obsessed with eating only Shaker-made whole wheat bread that he was known to travel with his own supply of bread. Even when he made a missionary trip to England to lecture on Shakerism in 1871, he packed Shaker bread for the trip. James M. Peebles, a well known Spiritualist who was closely associated with the Shakers, accompanied Evans on the tour. He reminisced, “On the morning we were to breakfast with the Hon. Mr. H, the Elder took his plain breakfast at the usual hour. Much of this he had brought with him in a large trunk from Mount Lebanon. When about to start, the Elder deliberately walked to his trunk, took out a good sized chunk of cold, coarse-ground Shaker unleavened bread, which, putting into his satchel, we started off for our appointed breakfast. Ten or twelve guests met in the elegantly appointed breakfast room. The Elder had stepped to his grip, taken out his bread, half as large as a quart bowl, and sitting down at the table, laid it by his plate. As the Elder was the honored guest, tall and reverential looking, the host asked him to ‘say grace.’ Crossing his hands and sitting as erect as a towering pine, he said, ‘In my accustomed way,’ and this way was as silent as the depths of silence itself. … Soon there was passed him a cup of coffee. He did not take coffee. ‘Do you prefer tea, or cocoa?’ ‘Nay, I take neither.’ There was passed to him a nice plate of fish. ‘Nay, I do not take fish.’ ‘Perhaps you would prefer steak?’ ‘Nay, I do not take steak, or any animal flesh.’ ‘Well, really Elder, what do you eat and drink?’ ‘I drink water when thirsty, and I brought my bread with me, for I did not expect to find any London bakers’ bread that was fit to eat.’” (Eldress Anna White and Sister Leila S. Taylor, Shakerism, Its Meaning and Message. Columbus, OH: Fred J. Heer, Publisher, 1904.)

It was this conviction that good health depended on good bread. The Museum will be pleased to hear from anyone willing to bake up some of Elder Evan’s “good bread” and offer his or her opinion of the loaf.