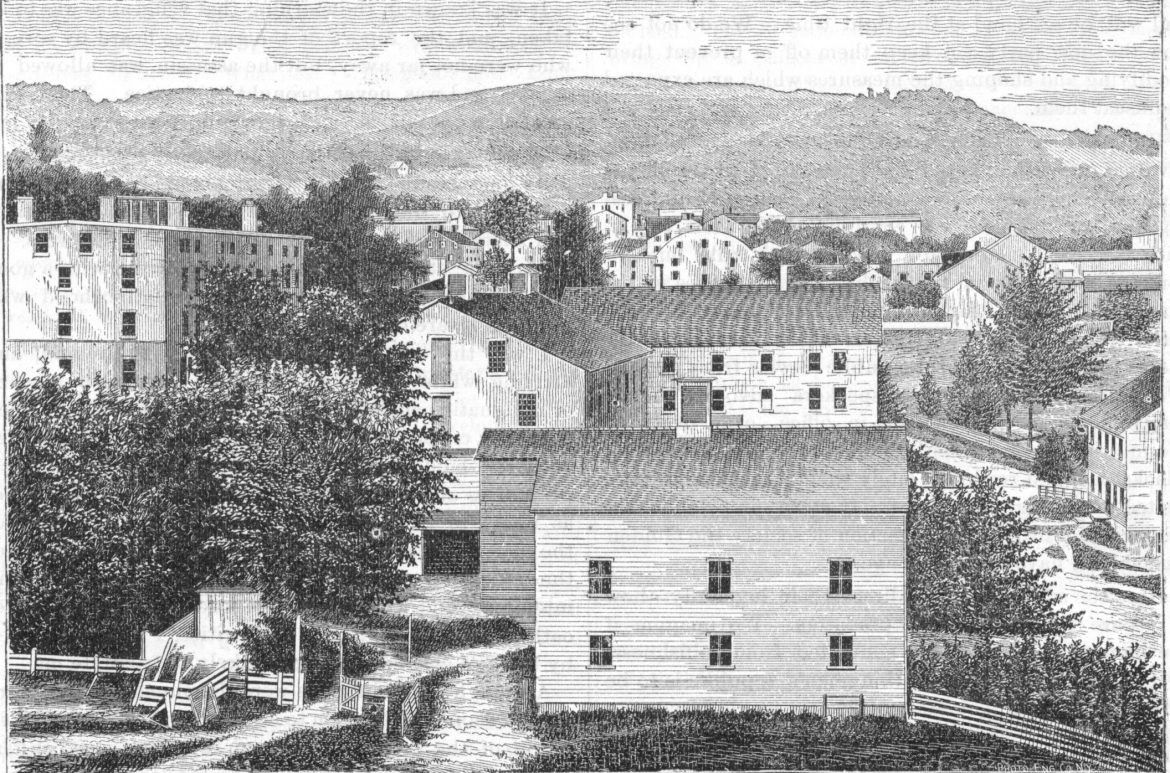

“North Family Shakers,” Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1880. Published in The American Socialist where it was engraved after n 1871 stereographic photograph by James Irving, Troy, NY.

Across from Shaker Museum’s Old Chatham campus is a beautiful field of rye grass. The season when farmers are moving from the summer’s haying into the fall’s harvest of grains is fast coming upon us. The kernels on the spikes of rye are filling out and soon will turn the color that signals the right […]

Across from Shaker Museum’s Old Chatham campus is a beautiful field of rye grass. The season when farmers are moving from the summer’s haying into the fall’s harvest of grains is fast coming upon us. The kernels on the spikes of rye are filling out and soon will turn the color that signals the right time to harvest. This rye field will one day be harvested, dried, fermented, and distilled into rye whiskey – unlike the Shakers at Mount Lebanon who grew rye, along with corn, oats, barley, and wheat, for human and animal consumption – consumption without the magic of fermentation and distillation.

At the North Family at Mount Lebanon, the Shakers grew enough of these grains to have a purpose-built structure – a granary – just for its storage. The North Family Granary, a two-story building with a large attic and a full cellar, was built in 1838 and still stands today. The Granary is distinctive in two aspects: it has a shaft attached to the front of the building to convey bags of grain by way of a manpowered hoist to its upper floors – a grain elevator – and it was constructed with solid shutters on its north and south sides and glazed windows only on its east and west sides. These shutters were likely left wide open in acceptable weather to help regulate the humidity and heat that was often produced by grain being stored before it was thoroughly dry – a subject of much discussion in the agricultural world in the mid-nineteenth century. It also had a large cupola in the center of the roof for additional ventilation. The building was originally finished with vertical sheathing over its heavy timber frame and was painted a dark red. Its roof was covered with pine shingles. Before the early 1870s the family covered the sheathing with standard clapboards and the pine shingles with slate.

In the fall of 1871 a major renovation of the Granary took place. The entire building had four or five grain bins built on each floor and each bin had a wooden chute that conducted grain from that bin to the first floor. Grain could be drawn from any bin by sliding open a small wooden gate. Grain could then be mixed for feed or brought from a bin for sifting. The cupola was removed in the fall of 1873. The cellar of the Granary was not intended for grain storage, but was used extensively for the storage of root crops – carrots, beets, turnips, and potatoes. While the cellar served well for this purpose, ten days after the famous March 11, 1888 blizzard, with an ensuing thaw and rain, the cellar flooded to a height of four feet – causing the Shakers to add a drain to the cellar floor several years later.

In 1821 the North Family recorded their grain harvest as “30 Bushels of wheat, 250 of Rye [and] 130 of Oats.” In the next decade the family increased considerably both in membership and land holdings making it logical that they would need more space for an increase in the grain they needed to grow. Although the new Granary seems like a large space for grain, in fact, in 1846 the North Family built a second, albeit smaller, grain barn attached to their sawmill’s lumber shed. This building, in addition to providing more storage for grain, was close enough to a source of waterpower to enable the use of a power threshing machine. By the early 1880s the North Family was still raising a substantial quantity of grains as is recorded on December 11, 1882 in one of its family journals:

Rather mild; some snow fell during the day with some wind. Thrashing; finished it all up; got 70 bus. of barley & oats to 4 loads of straw. The yield of grain on the home farm had been as follows:

244 bus. of wheat, making about 22 bus. to the acre;

189 bus. of rye, making about 30 bus. to the acre;

240 bus of oats, making about 40 bus. to the acre;

210 bus. of barley, making about 35 bus. to the acre;

883 bus. in all, besides corn from 2 acres, which will probably fill up the 1000 bus.

The Granary appears to have been in use and kept in good order until the Shakers vacated the North Family property in the fall of 1947. It subsequently was owned by several individuals as well as the Darrow School. In the 1980s it was leased to a woodworker who used the building for his business of making replicas of Shaker furniture and in the 1990s it became a reception and exhibition space for a not-for-profit that interpreted the history of the North Family. With funding from a Save Americas Treasures grant from the National Park Service, Shaker Museum worked with architects to document the Granary. The documentation was completed in 2004 and that information has been included in the Historic American Buildings Survey maintained by the Library of Congress.

North Family Granary, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1920s. Photograph by William F. Winter for the Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress, Washington DC. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny0537.photos.115512p/resource/ on July 5, 2022.

Following the documentation, the Museum then sought to restore the building. Between 2006 and 2009, in collaboration with the American College of Building Arts in Charleston, North Carolina, the Historic Preservation Program at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, and the North Bennet Street School, Boston, Massachusetts, deteriorated and missing parts of the timber frame, sheathing, window shutters, gutters and downspouts, and its slate roof were all addressed while providing students hands-on experience in preservation carpentry. The Shaker Museum continued to use the building as a reception and exhibition space until shortly before the COVID pandemic.

Restoration of North Family Granary, Mount Lebanon, NY. 2006. Boyd Hutchison, Photographer.