While reviewing photographs taken at the Mount Lebanon North Family as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey, we noticed an image showing the attic of the Wash House that provided definitive provenance for an artifact in the museum’s collection, and confirmation that a medical practice common in the outside world was also practiced by […]

While reviewing photographs taken at the Mount Lebanon North Family as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey, we noticed an image showing the attic of the Wash House that provided definitive provenance for an artifact in the museum’s collection, and confirmation that a medical practice common in the outside world was also practiced by the North Family Shakers.

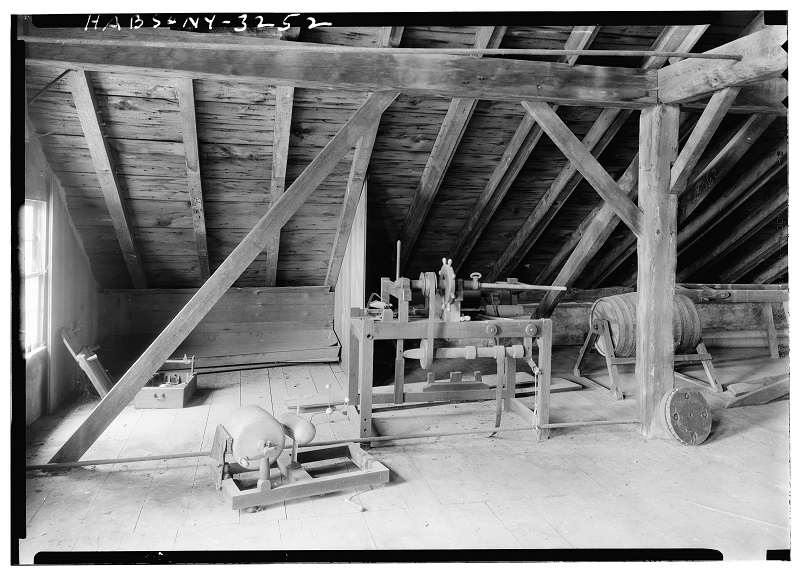

This photograph was taken by William F. Winter, Jr., in the 1920s, and is now part of the Historic American Buildings Survey collection in the Library of Congress; it can be found on their website here. It shows at the center left foreground an incomplete electrostatic machine; another can be seen at left rear, just behind a beam. This tells us that electrostatic treatments, which were practiced by several other Shaker families, were performed at the North Family as well.

Electricity began to be used as a medical treatment in the mid-18th century for ailments such as headaches, toothaches, and joint pain, though its effects were little understood and it was difficult to control. There is evidence that Shakers at the Mount Lebanon Church family underwent electrostatic treatment, even if they did not make or possess a generating apparatus. On October 6, 1856, Eldress Polly Reed wrote in a journal, “Saturday 4th there came here from New York a strange kind of a woman who wanted to stay awhile & get some acquainted & make engagements for some roots & herbs. She seems to be an old fashioned doctress, is very loquacious. Says the Shakers are her friends, & she has a right to tell them any thing that she pleases. I told her my case relative to the disease in my head. She says nothing will do me any good but to use the water as I do, & magnetized electricity two or three times a week. To day she tried the electricity on me to show our doctors the proper manner of applying it.” Three days later, Eldress Polly wrote that she “went over to the South House with Charity Vance, (the doctress woman) to see Hannah Ann & others of their feeble ones. Tho before going she electurized [sic] me as she did the Monday previous.” Perhaps if Ms. Vance taught the family’s physicians to apply electrostatic treatment, the family owned or planned to make or acquire a machine.

Though neither of the electrostatic generating devices seen in the HABS photograph are known to exist, the museum does have in its collection an electrostatic machine made in 1810 by Brother Thomas Corbett, a trained physician for the Canterbury Church Family Shakers. It is interesting to note that a small handwritten label found with the machine states that it was “A decided improvement upon that of 1800,” demonstrating that it was not the first machine made, and that the practice of electrostatic treatments had been undertaken for at least a decade in Canterbury.

The operator of the machine turned a hand crank which rotated the glass cylinder. Friction was generated by the glass passing the surface of a cushion; the metal comb at the other end collected the static charge and conducted it to the vertical jar, called a Leyden jar. Wires attached to the Leyden jar, which terminated in wands, conducted the static electricity to the patient at the point of contact. The sensation experienced by the patient was what one might feel touching a light switch or door knob in a dry environment, although presumably it took extensive experimentation and refinements to consistently achieve that effect.

An electrostatic machine very similar to the one made by Brother Thomas Corbett is in the collection of the New York State Museum, Albany, NY. According to a handwritten inscription, it was made by Brother Frederick Wicker of the North Family, Watervliet, in 1822.

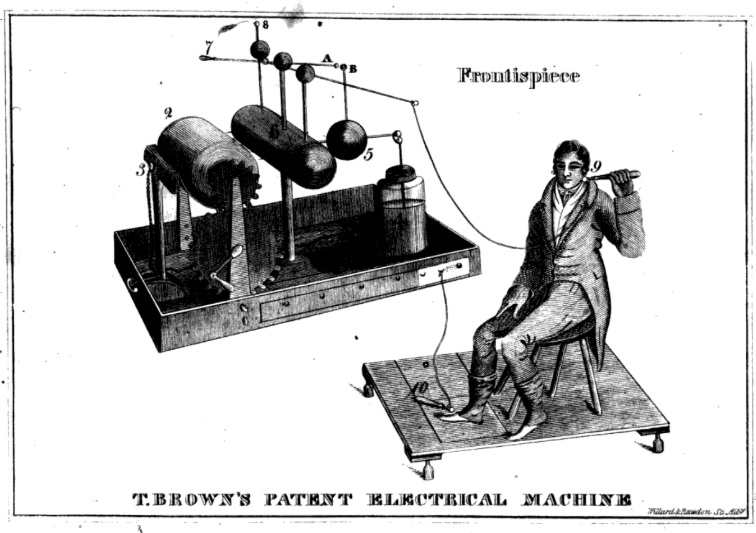

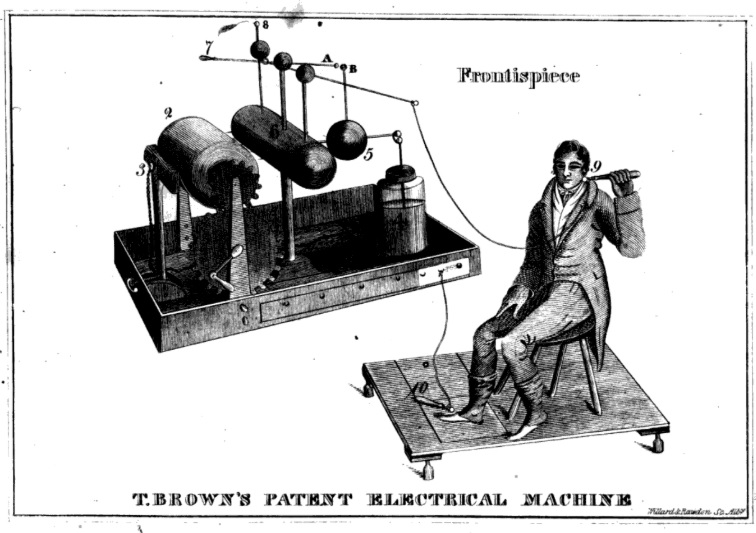

Each of these are similar to a machine illustrated in an 1817 publication, The Ethereal Physician: or Medical Electricity Revived, written by Thomas Brown. The frontispiece of Brown’s book shows a person seated on a kind of stand or platform, holding at his neck a wand which connects by a line to the electrostatic apparatus.

Interestingly, Brown had once been a Shaker, and wrote a book about his experience called Account of the People Called Shakers. Brown claimed in The Ethereal Physician that he’d long been a sufferer of back pain, rheumatism, respiratory ailments, headaches, and deafness and tinnitus in one ear, and that his ailments were “restored to health by the use of Electricity” or, as he also refers to it, the “electrical fluid.” He also claimed that electrical static was of “unquestionable use” in the treatment of blindness, bruises, coldness in the feet, consumption, cramps, epilepsy, gout, hysterics, inflammation, back and stomach pain, heart palpitations, sore throats, and toothache.

The last valuable piece of information provided by the HABS photograph can be seen at the left rear of the room, adjacent to an electrostatic device. It is a stand or platform, rectangular, with a semicircular piece attached at the end. The platform was used to administer electrostatic treatments; a chair upon which the patient sat was positioned on the stand, and the patient’s feet rested on the rounded end portion. The feet of the platform were made of the necks of glass bottles, sawn or cut to a height of about 4 inches. This platform, we decided upon examination of the photograph and the object, is in the museum’s collection.

The platform was found in the museum’s collections storage and catalogued in 2008, but museum staff was unable to determine its provenance, meaning where it originally came from. Though most of the objects in the museum’s collection are documented with written records, some lack documentation and require more investigation or simply well-founded guesses. Spotting the chair platform in the HABS photograph demonstrated that it was indeed owned and used by the North Family Mount Lebanon Shakers, an important piece of information that adds to the historic significance of this artifact, and adds to the story of the medical care practices of the Shakers.

To All you Saints at Shaker Museum, I appreciate you steady scholarship. You continue to recharge our nation’s idealism

Could Brother Jerry please send a few Shaker volts to my Son’s Tesla?

Thank you, Brother Tom!