Group of Shakers on Meetinghouse Steps, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1888, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1960.12205.1. James Irving, photographer.

Since the invention of photography, decisions made by the photographer about printing and mounting affect the final appearance of the image, sometimes introducing variations in images made from the same negative.

Since the invention of photography, decisions made by the photographer about printing and mounting affect the final appearance of the image, sometimes introducing variations in images made from the same negative. Institutions often collect multiple versions of what appear to be the same image, for the stories told by these variations.

Derobigne Mortimer Bennett, a Shaker brother who left the Church in the 1840s, is best known as one of the most prominent freethinkers of the late nineteenth century. As the founder, editor, and publisher of the weekly journal The Truth Seeker, Bennett was such a prolific writer that he could have filled every page of The Truth Seeker with his own writing. He was so verbose, in part, because he would often write a sentence and, not quite liking how he wrote it, rewrite the sentence, maybe several times – each time letting all previous iteration of the thought stand for publication.

In a similar vein, James Irving of Troy, New York, an early itinerate photographer who was responsible for a large body of work that provides valuable documentation of the Watervliet and Mount Lebanon Shaker communities, would apparently make several photographs of the same scene, and, being unable to decide which image he preferred, print several versions of the same subject.

Irving’s first photographs of Shaker subjects were stereographic views. The earliest stereographs date from 1868 at Watervliet and 1869 at Mount Lebanon. At the end of January 1870, the Shakers at the Church Family noted in their family journal that, “James Irving, of Troy comes to Lebanon and brings a large number of pictures he has taken of New Lebanon Shaker Village.” The Shakers, apparently pleased with his work, purchased stereographs from him to sell in their stores. In April, 1871 they bought, “20 1/2 Doz Stereoscopic views of J. Irvin[g] – $33.00.” He continued to photograph the Shakers through the 1880s, creating both stereographs and the increasingly popular cabinet cards.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”6″ gal_title=”Devil in the details: Comparing photographic images”]

One of Irving’s earliest stereographs is of the Shaker and biological sisters, Cornelia Charlotte Neale and Sarah Neale. This image was likely taken at the North Family at Watervliet, where both of these young Shakers lived by the mid-1860s. Irving created at least three different versions of this view and, while he may have had a favorite, printed, mounted, and sold all three versions (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig 3). In these three versions of Irving’s photograph of the Neales, one can almost hear the him giving instruction to his sitters, “Sister Sarah, please lift your right hand to your face – good – now Sister Cornelia, you do the same with your left hand – perfect – and let’s just try one where both of you keep your arms crossed in your laps – bravo!”

Shaker School room, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1875, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1951.4388.1. James Irving, photographer.

Shaker School room, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1875, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 2011.23010.1. James Irving, photographer.

This example provides a good example of why institutions might collect what may appear to be multiple copies of the same photograph – they are not always the same photograph — in the examples above another reason for collecting duplicate copies of photographs is apparent. It seems to be common in the production of stereographic views that the printing, cutting, and mounting of an image may be different enough that one version may contain information not present in another. In this example, the persons doing the printing, cutting, or mounting chose in one case to include the ceiling of the Church Family’s girls’ school, while at some later or earlier time a decision was made not to include the ceiling. Occasionally, people on the edges of the photographs appear or disappear.

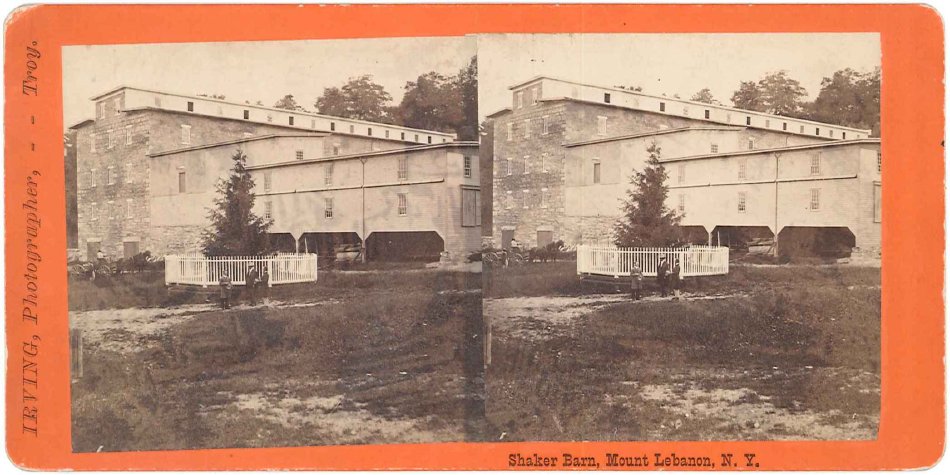

Shaker Barn, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1870, Hamilton College, Special Collections, Shaker Collection. James Irving, photographer.

Shaker Barn, North Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, ca. 1870, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1968.16563.1. James Irving, photographer.

In Irving’s iconic photograph of Mount Lebanon’s North Family Stone Barn, one version includes three Shaker men standing with the barn in the background. A wagon has apparently just entered the picture from the left. In a second image, the wagon has moved on, one of the men seems to have walked back to lean on the picket fence, and two Shaker sisters have joined the scene. In this case, it appears to have become a photograph of the North Family’s Elders Lot – Elder Frederick Evans and Brother Daniel Offord with Eldress Antoinette Doolittle and her helpmate, Sister Anna White.

Group of Shakers on Meetinghouse Steps, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1888, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1950.4012.1. James Irving, photographer.

Group of Shakers on Meetinghouse Steps, Church Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1888, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1960.12205.1. James Irving, photographer.

When Irving began creating photographs in the cabinet card format, his photographs became more consistent. However, one example (Fig. 8), a scene in which he gathered brothers and sisters from the Church Family on the south steps of the Meetinghouse for a “group shot,” provides another example of how duplicate photographs may provide insight into the working habits of a photographer. In one version of this scene, the little girl seated on the step appears to have moved her arm. Probably sensing that this may have spoiled the image, Irving asked his subjects to “hold that pose” while he reloaded a glass plate into his camera and made a second image. The second image (Fig. 9), except for the little girl’s arm not being blurred, is so close to the first one has to be amazed that the Shakers could hole their poses so precisely. Careful examination does show slight changes in the sitters’ positions, but not so much that, without the blurred arm, anyone would think the photographs were created from two separate plates.

There is reason to be careful not to assume that because two photographs look the same they are. Only when institutions collect multiple copies of these images – or make them readily available online – can these comparisons be made.