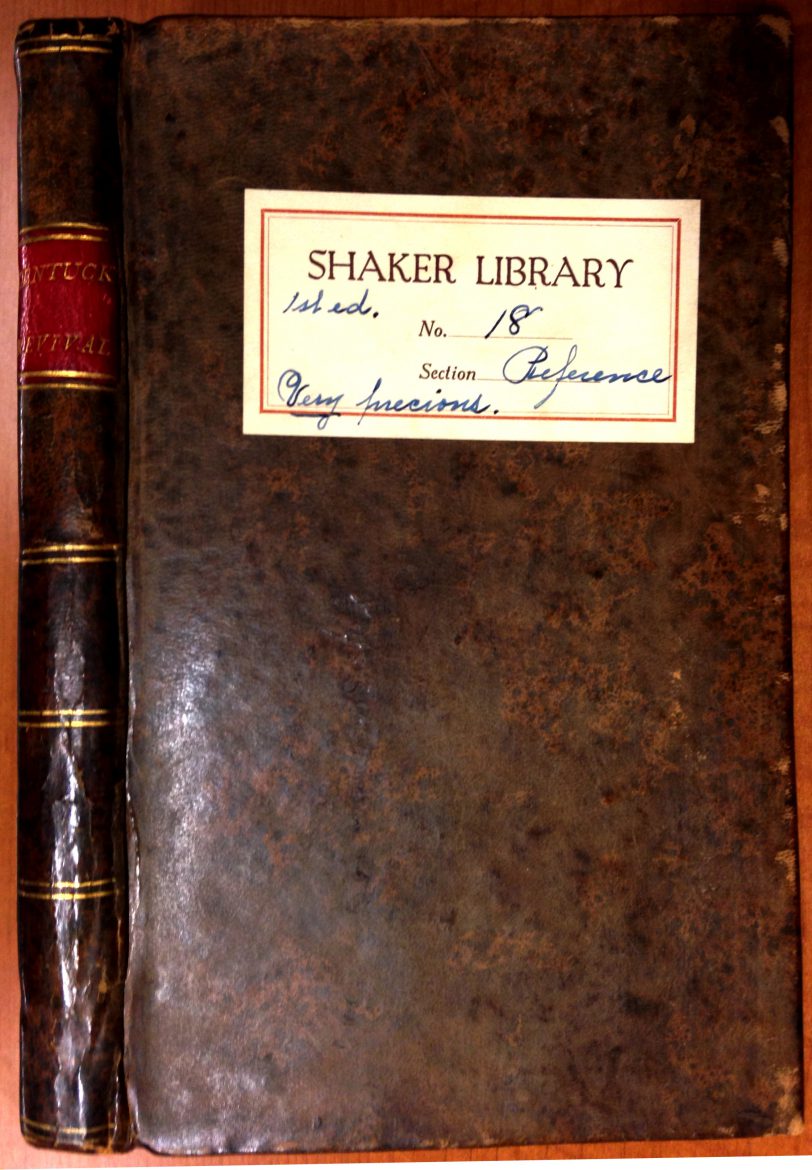

The Kentucky Revival or, A Short History of the Late Extraordinary Out-Pouring of the Spirit of God, in the Western States of America, Agreeably to Scripture-Promises, and Prophecies concerning the Latter Day: With a Brief Account of the Entrance and Progress of What the World Call Shakerism, Among the Subject of the Late Revival in Ohio and Kentucky. By Richard M’Nemar. Cincinnati, OH: From the Press of John W. Browne, 1807. Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1962.12000.1

This book and its author, Elder Richard McNemar, are significant to the history of the Shakers. Four or five editions of the book were published by the Shakers prior to the Civil War and McNemar has been the subject of two biographical works: A Sketch of the Life and Labors of Richard McNemar (1905), by John Patterson McLean, and Richard the Shaker (1972) by […]

The Kentucky Revival or, A Short History of the Late Extraordinary Out-Pouring of the Spirit of God, in the Western States of America, Agreeably to Scripture-Promises, and Prophecies concerning the Latter Day: With a Brief Account of the Entrance and Progress of What the World Call Shakerism, Among the Subject of the Late Revival in Ohio and Kentucky. By Richard M’Nemar. Cincinnati, OH: From the Press of John W. Browne, 1807. Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1962.12000.1

This book and its author, Elder Richard McNemar, are significant to the history of the Shakers. Four or five editions of the book were published by the Shakers prior to the Civil War and McNemar has been the subject of two biographical works: A Sketch of the Life and Labors of Richard McNemar (1905), by John Patterson McLean, and Richard the Shaker (1972) by Hazel Spencer Phillips.

Richard McNemar was born in 1770 in Tuscarora, Pennsylvania, and moved around considerably with his family. He was the youngest and though he worked his father’s farm as needed, was allowed to get a decent education. By age 18 he became a teacher. His quest for more education put him in association with ministers in the Presbyterian Church. Learning Latin, Hebrew, and Greek by the time he was in his early twenties he was preaching sermons in and around Cincinnati, Ohio, and by the turn of the nineteenth century he had located in Western Kentucky near what eventually became the Shaker community of South Union. McNemar and several other Presbyterian ministers ran afoul of the church by endorsing a free will doctrine in opposition to church teachings. He, with others, was dismissed from his pulpit. A new movement, a revival, was taking place in the area, largely initiated by the Reverend John Rankin. It was known by physical phenomena. Fascination with “The bodily agitations or exercises, … called by various names: —as the falling exercise—the jerks—the dancing exercise—the laughing and singing exercise, etc.,” brought together tremendous crowds. Too large for meetinghouses, these gatherings were held outside in large camp meetings. The first significant camp meeting was held under the direction of McNemar at Cabin Creek, Kentucky. It lasted four days. When these meetings were reported in the press and the Shakers read the reports, they determined to send three missionaries from New Lebanon to investigate and see if there might not be an opening for them to share the gospel of Christ’s second appearing. When the missionaries arrived in the neighborhood of the revivals, they knew that in order to have a chance of establishing Shaker communities in that area they must make converts of the most influential of the revival preachers. They set their sights on McNemar and in the early spring of 1805, they found him at Turtle Creek, Ohio (what eventually became the Shakers’ Union Village) and were successful in their effort. In fact, McNemar brought nearly his entire congregation with him into the Shaker Church.

The Kentucky Revival or, A Short History of the Late Extraordinary Out-Pouring of the Spirit of God, in the Western States of America, (title page) … By Richard M’Nemar. Cincinnati, OH: From the Press of John W. Browne, 1807. Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1960.12000.1. Staff photograph.

McNemar wrote his history of the Great Kentucky Revival during his first two years as a Shaker. McNemar himself comments to his readers (whom he likely expected to be Shakers), “You have been probably waiting for something to be published from this quarter, and may be a little surprised to find the Kentucky Revival our theme; as it is generally known that we profess to have advanced forward into a much greater work. Admitting this to be the case … we believe it [the Kentucky Revival] was nothing less than an introduction to that work of final redemption which God had promised, in the latter days. And to preserve the memory of it among those who have wisely improved it as such, the following particulars have been collected for the press.” It is not unreasonable to think that McNemar was working on such a history prior to his introduction to the Shakers. This seems supported by McNemar’s inclusion of some extraneous materials with the book.

McNemar’s history of the Kentucky Revival appears in chapters one through four of the book. A second part of the book with separately numbered chapters one and two appear under the subtitle, “The Entrance &c. of Shakerism.” Following this short introduction to the Shakers, McNemar includes an essay titled, “A Few Reflections”; an appendix “Containing a short account of a work of the good spirit among some of the neighboring Indians”; and finally a separate book bound with the Kentucky Revival titled, Observations on Church Government by the Presbytery of Springfield to Which Is Added, the Last Will and Testament of that Reverend Body.”

The Kentucky Revival or, A Short History of the Late Extraordinary Out-Pouring of the Spirit of God, in the Western States of America, (detail of presentation inscription) … By Richard M’Nemar. Cincinnati, OH: From the Press of John W. Browne, 1807. Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1960.12000.1. Staff Photograph.

The copy of the first edition of The Kentucky Revival (1807) in the collection of Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon is identified on its library label by its Shaker owners as – “Very precious.” It is not only the first edition, it is the first bound publication of the Shakers. In addition it is a presentation copy from the author to the leader of the Shaker Church at the time of its publication, Mother Lucy Wright. The front free endpaper bears the following inscription: “This Book is a present to Mother from Richard. It is written according to the sense of the people in this country – many expressions that are well understood here among the people at large, on account of the many overturns in religion that have been here, may appear dark and mysterious to many people in the Northern States.”

The Museum’s copy of The Kentucky Revival was retained by the Lebanon Ministry. When Mount Lebanon closed in 1947, it was sent, along with many other treasured books and manuscripts, to be kept by the Canterbury Ministry. There it was added to the community’s Shaker Library by Elder Irving Greenwood and Sister Aida Elam in the 1930s. It was acquired by the Museum in 1960 as the Shaker Museum’s founder John S. Williams, Sr., started to gather materials for a new library collection.