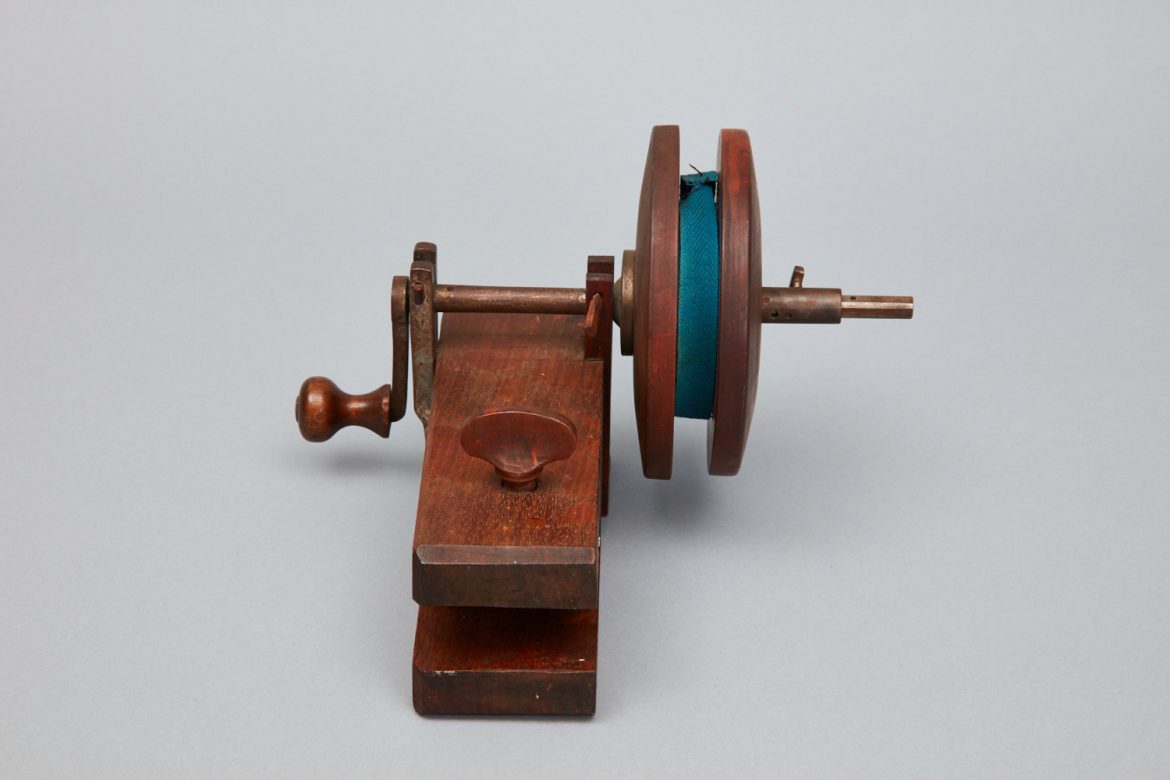

Bandage Roller (end view), Church Family, Canterbury, NH, Ca. 1840, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1953.6368.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

At Mount Lebanon in 1866, Brother Elisha D’Alembert Blakeman wrote a eulogy to recently departed Brother Isaac Newton Youngs. He said, “His mechanical genius was remarkable … Very many of our little conveniences which added so much to our domestic happiness owe their origin to B[rother] Isaac.” Although Brother Isaac had nothing to do with the invention or making of this […]

At Mount Lebanon in 1866, Brother Elisha D’Alembert Blakeman wrote a eulogy to recently departed Brother Isaac Newton Youngs. He said, “His mechanical genius was remarkable … Very many of our little conveniences which added so much to our domestic happiness owe their origin to B[rother] Isaac.” Although Brother Isaac had nothing to do with the invention or making of this winding device, Brother Elisha’s words ring true for a number of Shaker brothers – often identified as “mechanics” – who had similar roles in other communities – brothers such as Thomas Corbett at Canterbury or Brother Micajah Burnett at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky. From the brains and workshops of these Shakers, there seem to be an almost endless stream of “little conveniences” intended to make work more pleasant and efficient. This winding device is a good example.

Bandage Roller (side view), Church Family, Canterbury, NH, Ca. 1840, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1953.6368.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

When the Shaker Museum acquired this device from the Canterbury Shakers in 1953 it was identified as a bandage roller and it was displayed in the Museum’s medical department exhibit without a bandage wound on it. The wooden wheels mounted on the winding shaft are adjustable. By turning a small thumbscrew the distance between the wheels can be set from zero to two inches. While this adjustment is appropriate as bandaging materials could certainly vary in width, it makes one think that it would also be an appropriate tool for winding all kinds of narrow materials – bonnet edging, carpet binding, strapping, and even short pieces of chair webbing – in fact, at present the winder has a short piece of chair webbing on it. Once the bandage or other narrow material is wound into a roll the outer wheel can be removed and the roll slid off the iron shaft. The winder is made all the more convenient by having a notch cut out of one end that can be slipped over the end of a table or work desk and secured with a wooden threaded screw. Whatever the maker of this device though he was making – bandage roller or something else – it may have been taken around from shop to shop whenever something relatively short and flexible needed to be rolled up.

Bandage Roller (end view), Church Family, Canterbury, NH, Ca. 1840, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1953.6368.1. John Mulligan, photographer.

The piece was clearly made with much thought and care. The metal shaft turned by the handle and the collars that hold that hold the disks to the shaft appear to have been made on a metal lathe, and the support on which the shaft rests and the handle were forged by a blacksmith. The screws that hold this forged plate to the device are helpful in providing a “made before” date for the piece. In general, metal screws with screwdriver slots that are not precisely centered on the head of the screw were made before the invention of automatic screw-making machinery in the late 1840s. Several of the screwdriver slots on the roller appear to have been hand cut during the period before mechanization of the process took hold.

In a Shaker community, with a variety of skilled crafts persons available to assist on projects, it was probably easier to conceive of and complete projects that required several different skilled people than it would have been in the outside world. This little device could have required the work of a joiner to make the base block; a turner to make the wheels, threaded screw, and knob on the handle; a blacksmith to fabricate the iron support shaft and the handle; and a machinist to turn the shaft, collars, and possibly even the screws. As it was common for Shakers to have been trained in several different trades, it is possible that one brother identified as a “mechanic” could have made all of these varied parts.