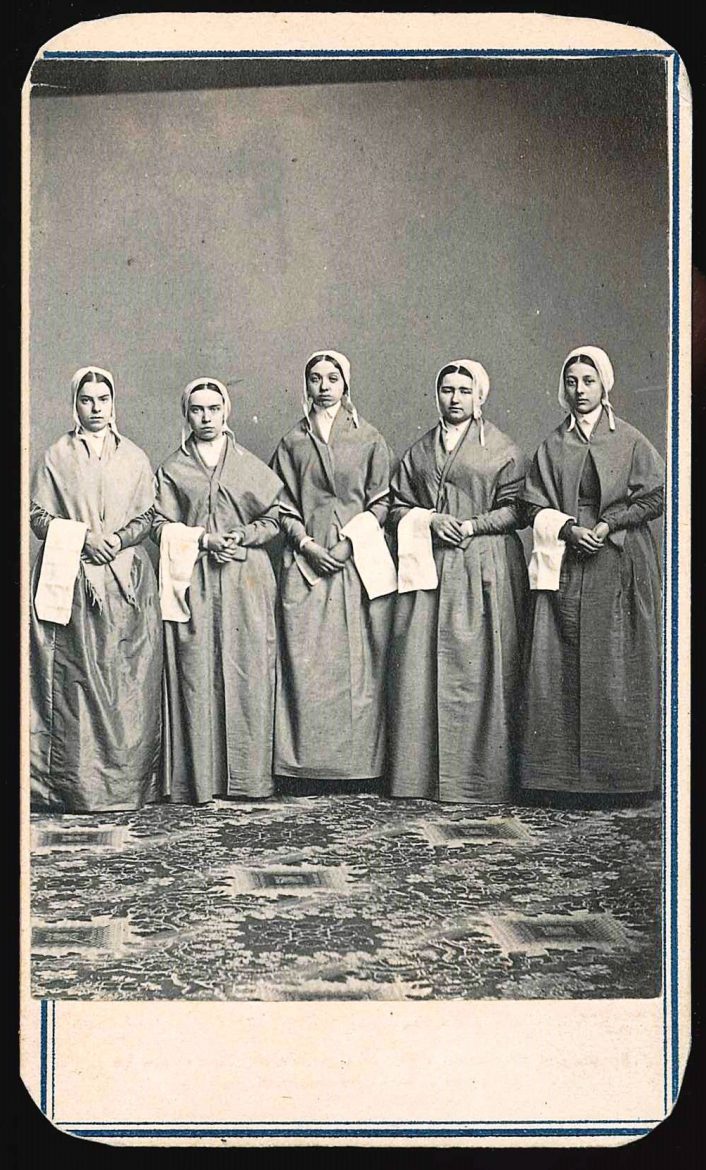

Carte-de-Visite, “The Quaker (i.e., Shaker) Booth at Our Fair,” 1864, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon, Churchill & Denison, photographers. 2017.24233.1

This intriguing carte-de-visite shows five women standing in a semi-circle in Shaker costume. On the back is written, “The Quaker [i.e., Shaker] Booth at Our Fair,” suggesting that the women pictured were the costumed volunteers that staffed the Shaker booth at a fair. The fair was no ordinary event however, but rather a fair held in 1864 to raise […]

Carte-de-Visite, “The Quaker (i.e., Shaker) Booth at Our Fair,” 1864, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon, Churchill & Denison, photographers. 2017.24233.1

This intriguing carte-de-visite shows five women standing in a semi-circle in Shaker costume. On the back is written, “The Quaker [i.e., Shaker] Booth at Our Fair,” suggesting that the women pictured were the costumed volunteers that staffed the Shaker booth at a fair. The fair was no ordinary event however, but rather a fair held in 1864 to raise money to support soldiers wounded or taken sick in battle and their impacted families. There are two questions raised by the photograph: First, were these Shaker sisters? And second, how were the Shakers involved in the fair?

On June 18, 1861, the Federal Government created the United States Sanitary Commission as a private agency charged with serving wounded soldiers and supporting their families. The agency, based on a British model developed during the Crimean War (1853-1856), raised an estimated 25 million dollars. Much of that money was generated by a number of “Relief Bazaars” held around the country. These events, often lasting months or even years, were similar to large agricultural fairs – groups representing various ethnic, business, trade, and religious groups constructed and manned booths that showed a variety of objects and foodstuffs associated with each group. They were often manned by people dressed in costume appropriate to the theme of the booth.

“Diagram of the Fair,” The Canteen, February 22, 1864, p. 1. This diagram of the floor plan for the Relief Fair shows the location (highlighted in red) of the Shaker Booth.

Albany, one of the three major centers for mustering soldiers in and out of the Union Army in New York, was filled with sick and wounded troops that needed to be fed and doctored. Families who lost fathers and sons were destitute and needed care. The mayor of Albany, George Thatcher, formed the Citizens Military Relief Fund and the Ladies’ Army Relief Fund. These groups, in turn, organized the Great Sanitary Fair held in Academy Park on Washington Avenue. A special temporary building was constructed in the park in the shape of a great double Greek cross. There were booths representing the towns of Albany, Saratoga Springs, Schenectady, and Troy; booths representing Spain, Japan, Holland, Switzerland, France, Italy, and Russia; an Indian wigwam representing Native Americans; a “Gypsy” tent; and wedged between the American booth and the curiosity booth was a Shaker booth. They were all competing with each other to see which could raise the most money to support the troops. All manner of fund-raising took place. The most single exciting feature at the fair was an original draft of the Emancipation Proclamation donated by President Lincoln as the prize in a one-dollar-a-chance lottery. The winner donated it back to the Relief Fair and it was subsequently sold to the New York Department of Education with the understanding that it would not ever leave Albany. When the final draft of the Proclamation burned in the Chicago fire of 1871, the Albany copy became the only copy in Lincoln’s hand to survive.

Photograph, “Shaker Booth,” 1864, Albany Institute of History & Art, Churchill & Denison, photographers. Ser 30/106.

This carte-de-visite bears the name of the photographers on its back, Churchill & Denison. Rensselaer Emmett Churchill (1820 – 1892) and Daniel Denison (1814 – 1899) were active photographers in Albany between 1863 and 1869. They appear to have been the official photographers for the Relief Fair and a number of their photographs of the fair exist. A larger copy of the “sisters” from the Shaker Booth is in the collection of the Albany Institute of History and Art. That copy confirms that the women posed in the photograph are not Shakers. They are named as follows, left to right: Miss Mary Carpenter, Miss Emerson, Mrs. Frank Townsend, Miss Barns of New York, and Miss Abby W. Redfield. Had they been Shaker sisters posed in a photograph taken in 1864, it would have been one of the earliest surviving photographic images of Shakers. The Shakers’ support and involvement in the Relief Fair is more elusive. While there is no mention in the Watervliet Church and South Family journals of the event, a poem published in The Canteen, the official paper of the fair, suggests that the Shaker did support the effort. The poem reads, in part:

“Perish the thought I Let no man scold—

‘Tis for the lame and sick all—

Not silver seek we—nor yet gold—

Nor even the precious nickel—;

Premium forbid, But never mind—

Have you not goods or deeds?

New Lebanon forever kind,

Has sent in Garden Seeds —;

And Niskayuna not outdone

And moved by generous throes,

When asked for bread, would not give stone,

And sent a load potatoes—;

‘Twas mighty well—the sick must eat,

The garden must be planted—

And so the Shaker charity,

Was just the thing we wanted.”

These lines indicate that the Shakers at both Mount Lebanon and Watervliet made contributions to support the fair.

In this year in which Women’s Suffrage is being celebrated in New York State, it should be mentioned that these fairs were largely organized and manned by women. Dorothea Dix, well known for her work in prison reform and providing for the mentally ill, served as the superintendent for the fairs. She convinced the army medical corps that women could be of great value in its work. More than 1,500 women worked in hospitals – generally in nursing care, but also with surgeons, administering medicine, supervising feeding, cleaning beds, writing letters dictated by wounded men to their families, and general giving good cheer and comfort.

In all, the fair is supposed to have generated over 110,000 dollars, which against costs, provided over 80,000 dollars (well over $2 million in today’s dollars) to be used for direct service to soldiers and their families.