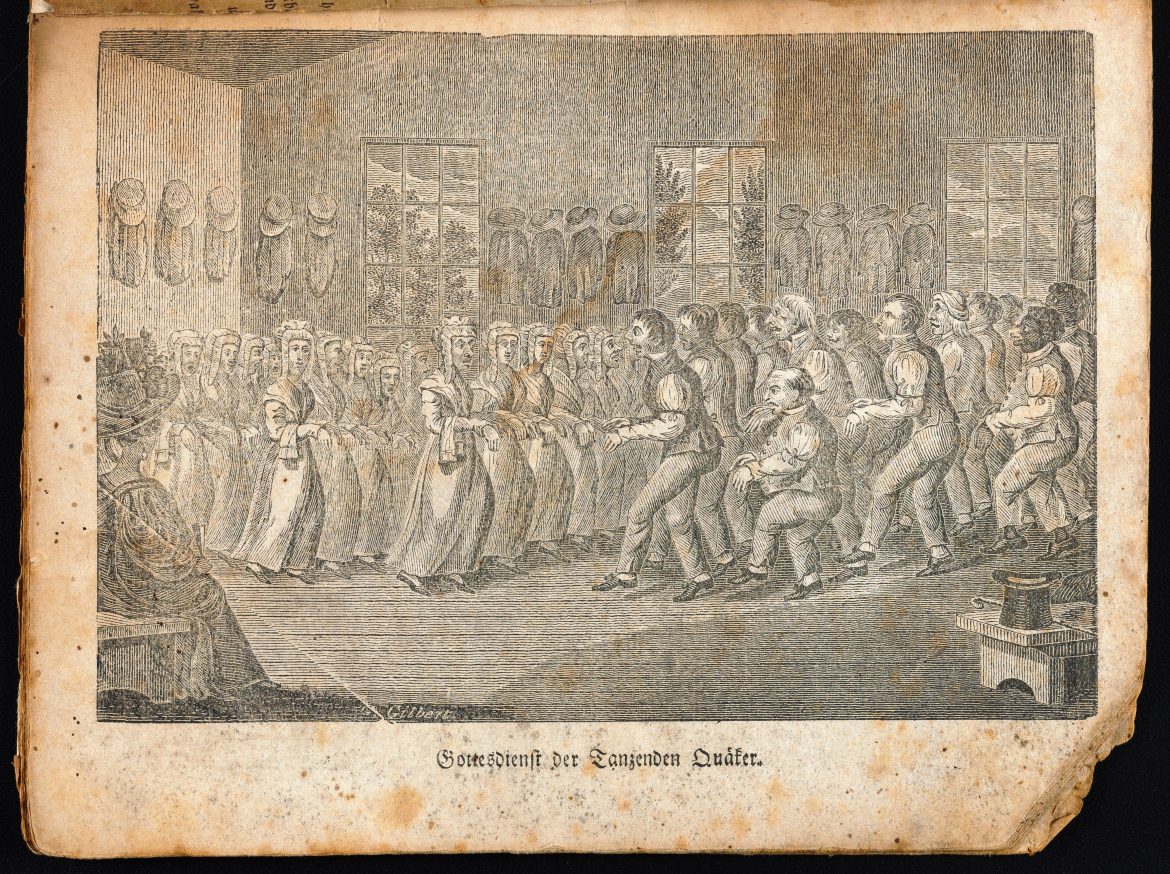

George Gilbert. “Gottesdienst der Tanzenden Quaker,” Amerikanischer Stadt und Land Kalendar auf 1831ste Jahr Christi. [Philadelphia: Conrad Zentler, 1830).

In 1976, Howard Finster, Baptist preacher and soon to be one of the grand old gentleman of American twentieth-century folk art, said that he was instructed by the Lord to begin painting “sermon art” because “preaching don‘t do much good; no one listens – but a picture gets on a brain cell.” From the time the Shakers […]

In 1976, Howard Finster, Baptist preacher and soon to be one of the grand old gentleman of American twentieth-century folk art, said that he was instructed by the Lord to begin painting “sermon art” because “preaching don‘t do much good; no one listens – but a picture gets on a brain cell.”

From the time the Shakers appeared on the scene in Manchester England in the mid-1700s, kind and unkind words poured onto the pages of newspapers and magazines as writers attempted to describe this peculiar new group of Christians. In 1774, these accounts followed them to the Colonies: the female Messiah – the dancing – the refusal to take arms – the denial of natural procreation. There was certainly ample material to write about, but unless one lived in proximity to one of their villages or happened upon one or two Shakers on the streets of cities such as Boston, New York, Cleveland, or Louisville, getting an image of a Shaker or a Shaker village “on a brain cell” was elusive. This was the case for the next six decades – until sometime in the late-1820s when an artist, apparently armed with pencil and sketchbook, attended the Shakers’ public meeting in New Lebanon, NY. There, in their new meetinghouse, a sketch of Shakers – separated by gender, arranged in ranks, performing their religious labors – was made and shortly after turned into a printable sheet.

George Gilbert. “Gottesdienst der Tanzenden Quaker,” Amerikanischer Stadt und Land Kalendar auf 1831ste Jahr Christi. [Philadelphia: Conrad Zentler, 1830).

Robert P. Emlen is a Visiting Scholar in American Studies at Brown University and a Fellow of the Massachusetts Historical Society. He recently retired as university curator and senior lecturer in American Studies at Brown, and as a part-time faculty member in the Theory and History of Art and Design at the Rhode Island School of Design. Emlen was so intrigued by this image that he dedicated over three decades to researching and writing about these illustrations, including the Shakers’ reaction to them and their eventual participation in having them created.

At the end of last year, a number of Emlen’s [Rob’s] articles about these illustrations published in a variety of journals were revised, enlarged, and with some new material added, brought together in a single volume, Imagining the Shakers: How the Visual Culture of Shaker Life Was Pictured in the Popular Illustrated Press of Nineteenth-Century America [Couper Press, 2019].

Emlen has had a long relationship with Shaker Museum and has made extensive use of its collection in his research for lectures, articles, and books. This year, he made a gift of his personal collection of these illustrations and supporting materials to Shaker Museum. He was a tenacious collector of illustrations – often collecting several copies of the same publication seeking better copies for high quality reproduction. While many of the illustrations exist in some form in most Shaker institutional collections, Emlen made it a point to acquire the illustrations before they were removed from their publications (as is often the case) – providing a context for how illustrations were used. Emlen’s gift includes illustrations by George Gilbert, John Barber, Joseph Becker, Arthur Boyd Houghton, and a number of unidentified artists. Of special interest are several versions of well-known illustrations that appeared in foreign-language publications.

Joseph Becker. “Die Shaker-Gemeinde in New-Lebanon, New-York: Sing-Hebungen der Shaker,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrirte Zeitung 32 (January 11, 1873), p. 8.

The inclusion of two German-language almanacs – one from 1831 mentioned above – and another from 1847 that includes the same George Gilbert wood engraving as does the 1831 almanac, along with a copy of a reduced-in-size and much simplified version of the same illustration that he created for the February, 1831 issue of Atkinson’s Casket, or Gems of Literature, Wit and Sentiment (later titled Graham’s Magazine), coupled with the Museum’s lithograph by Anthony Imbert from which Gilbert’s illustration was apparently copied, provide a wonderful look at the very beginning of the period in which Shakers were described in image as well as text.

George Gilbert. “Shakers Worshiping. (exercise), Atkinson’s Casket, or Gems of Literature, Wit and Sentiment 6 (February, 1831), inserted facing page 73.

One mystery in Emlen’s collection is an image of the Canterbury Shakers’ Church Family buildings viewed across some fields. The illustration is clearly printed from – possibly from the same wood engraving or a metal stereoplate cast from a mold made from the original wood engraving – an image first printed in The American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge in November, 1835. However, this copy is printed in blue ink with the phrase, “The Shaker Village, Canterbury, N. H.,” printed in red ink in the sky over the village. The image seems likely to have been produced as part of a label or an advertisement and not for publication in a newspaper or magazine, but its origin is not known for sure.

“The Village of the United Society of Shakers, in Canterbury, N. H.,” American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 2 (November, 1835), p. 133.

“The Canterbury Shaker Village, N. H.” [n. p., n. d.]

Bravo, Rob!!

Surely an amazing addition to the collection.