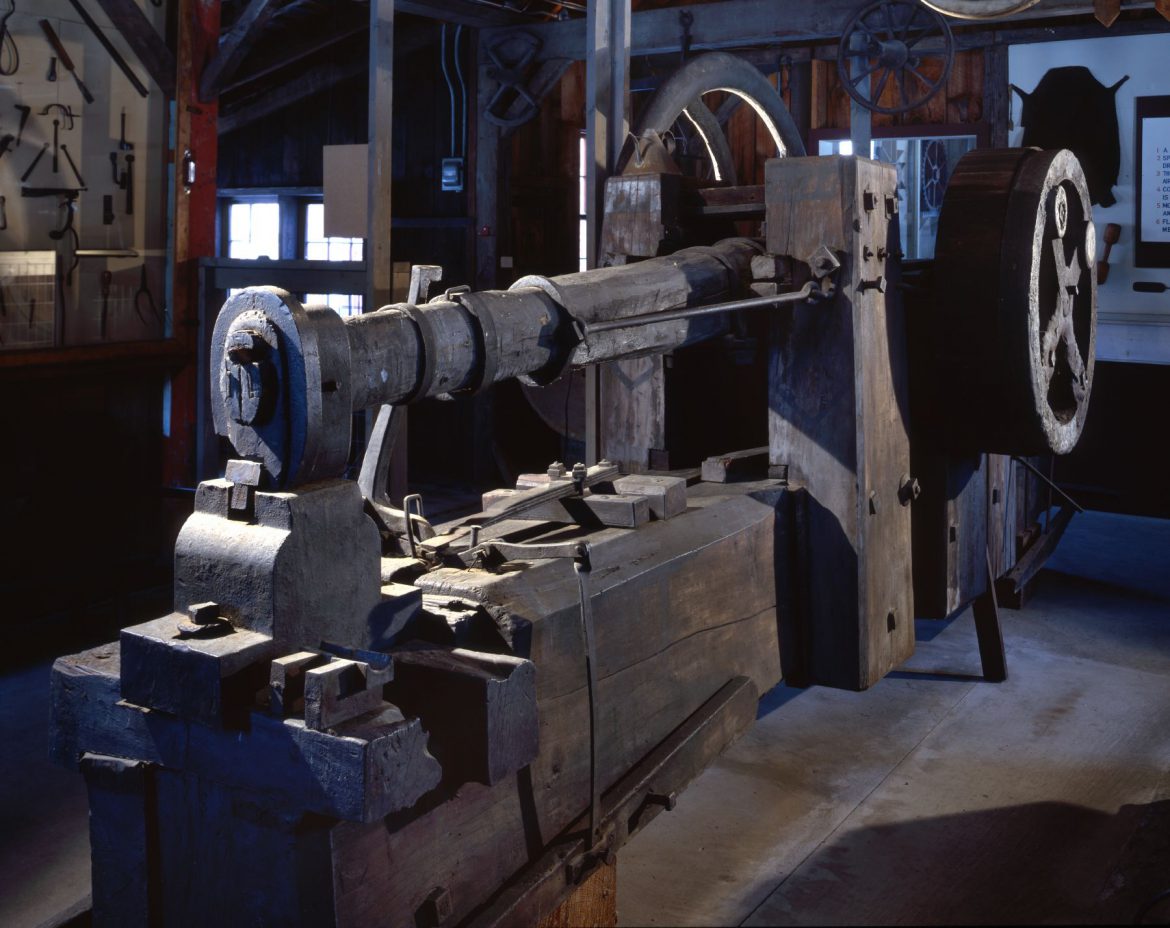

Trip Hammer on xhibition at the Shaker Museum, Old Chatham, NY, ca.1985, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon. Paul Rocheleau, photographer.

In the winter of 1846 the First and Second Order of the Church Family determined to build a new blacksmith shop, one of stone with waterpower that would operate a lathe, drilling works, a grindstone, bellows for the forge, and a trip hammer. The shop was to be built 34 feet by 44 feet and […]

Forge, Center Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 2016, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon. Staff photograph.

In the winter of 1846 the First and Second Order of the Church Family determined to build a new blacksmith shop, one of stone with waterpower that would operate a lathe, drilling works, a grindstone, bellows for the forge, and a trip hammer. The shop was to be built 34 feet by 44 feet and located in the corner of the Deming Lot at the northeast corner of the land bordered by the main road that ran through the village (now called Darrow Road) and the road that runs downhill to the Shaker gristmill (now called Ann Lee Lane on the east end and Cherry Lane on the west end). The shop still stands and is now a private residence. The 1845 Shakers’ census notes that there were three blacksmiths in what is now called the Center Family – Brothers Arba Noyes, James Vail, and George Long.

Construction was largely done by members of the Second Order with considerable help from hired Irish laborers who did much of the digging for the pit for the waterwheel and laid up most of the stonework. By mid-summer the wheel pit, the drain to carry away water from the wheel, and the masonry work were completed. In the early fall, the hired labor returned to build the dam to create the pond to supply water to power the shop. The dam is still standing and pond is on the east side of the road.

Interior of the Church Family Forge with the Trip Hammer in its Original Location, Center Family, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1940, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon. John S. Williams, Sr., photographer.

The decision to include a trip hammer in their new blacksmith’s shop was bold, but one that greatly increased the Shakers’ ability to fabricate and manufacture items out of iron. Trip hammers of many designs have been used for a couple of thousand years. The basic principle is that some kind of power is applied, in some manner, to raise a hammer larger than can be lifted by a man so that when it is dropped it will come down with more force than a man can exert alone. Trip hammers, in addition to forging iron, have been used for hulling and grinding grain, pounding rags for papermaking, and crushing iron ore to make it easier to extract the metal from the rock. In blacksmithing, trip hammers are often used to draw out flat sheets of metal from an iron bar and to shape a piece of square iron rod, for instance flattening the end of an iron bar to make a shovel and or making round ends on a square bar to make an axel for a wagon.

The Shakers documented their new trip hammer in their journals. In January 1846, Center Family Elder Amos Stewart experimented with a model for a windmill, hoping that he could use wind power “to tilt a triphammer.” This attempt, although it would have saved building a dam for the shop, apparently failed. The next month, Brother Hiram Rude, the family mechanic, went to Lee, Massachusetts to see a “gang of Triphammers.” The Shakers frequently went to visit businesses and factories to stay abreast of new technologies. Apparently in the next few weeks a design for the hammer was drawn up and casting patterns made for the metal parts. Elder Amos and Brother Peter went to Albany to see about castings for the gearing for the hammer. It was nine months later – after the new shop was finished and its forge fired up – that Elder Amos and Brother Braman Wicks, a carpenter from the Church Family, began working again on the gearing to drive the hammer. In July, a tree was cut for the frame to hold the hammer. Apparently by winter that year the Shakers were rethinking the design of the trip hammer. Elder Amos and Brother Hiram went to Cohose, New York, to look at another trip hammer and two days after that trip they had settled “upon the form for a Hammer & spoke for castings in Troy.” This final design was completed and the trip hammer seemed to be in use shortly after that.

While trip hammers were associated primarily with iron work, the Shakers appeared to have another idea for using it quite early on – maybe even before they began planning to built it: pounding black ash logs to break down the bond between the tree’s natural growth rings. When the growth rings are separated, they are easily peeled off in long strips and become the treasured materials from which baskets are woven. Most basket makers would do this work by pounding a log with a sledge hammer. For the Shakers, the ability to more efficiently produce basket weaving material meant that they could greatly increase their production of all kinds of baskets. In November of 1847, Elder Daniel Boler of the Church Family worked “at the blacksmith shop preparing trip hammer for pounding out basket stuff.” The Shakers were so dependent on having basket materials prepared by machine that in 1863, when apparently their own trip hammer was not available, they took ash logs to Bromley King’s forging shop in Waterford, New York, to get them pounded.

Trip Hammer on xhibition at the Shaker Museum, Old Chatham, NY, ca.1985, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon. Paul Rocheleau, photographer.

This trip hammer is among the largest and heaviest non-architectural objects made by the Shakers. It is over fifteen feet long, six and a half feet high, just over four feet wide, and is thought to weigh around four tons. The machine has two hammers – a large one at one end and a small one at the other end. It was powered by a waterwheel connected by a belt to the wooden drive pulley. Once the hammer got up to speed and the massive cast iron flywheel was rotating to preserve its inertia, one or both hammers could be engaged.

Watch a trip hammer demonstration from Thomas Ironworks, Seville, Ohio

Interior of the Blacksmith’s Shop Exhibition at the Shaker Museum, Old Chatham, NY, ca. 1955, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon. C. E. Simmons, photographer.

Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon’s acquisition of the trip hammer has some tales and legends associated with it. In the 1940s John S. Williams, Sr., the museum’s founder, heard that the Shakers were breaking up the equipment in the blacksmith’s shop in preparation for selling the building. He appealed to have the work stopped until he could move the hammer and the forge and bellows to the museum. It was war-time in America and the scarcity of trucks made it difficult to find someone who could move such a heavy piece of equipment. Fortunately, Williams’s good friend Albert Callan, the owner of the Chatham Courier newspaper, had a new printing press being delivered around this time and once the delivery of the press was complete the truck headed to Mount Lebanon to move the trip hammer. Once loaded, they then had to find a route back to the Museum that did not involve crossing a bridge that could not bear the weight of the truck and hammer. Somehow it all worked out and the trip hammer has been at the Shaker Museum ever since.